Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

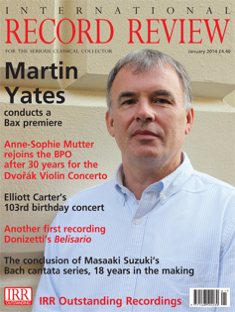

International Record Review - (01//2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Harmonia Mundi

HMC902172

Code-barres / Barcode : 3149020217221 (ID379)

For their second collaboration — after an outstanding Handel debut album, ‘Ombra cara’ (reviewed in January 2011), American countertenor Bejun Mehta and Flemish ex-countertenor René Jacobs turn their attention to ‘the rise of classical opera’ as the new disc is subtitled. Harmonia Mundi seems to imply that they are offering something of an historical perspective in this programme of arias by Gluck, Hasse, Traetta, Johann Christian Bach and the young Mozart. However, the sequence is, in fact, the now customary random jumble of arias, with no sense of chronology or development, so it’s the rise and fall and rise again of Classical Opera as we move from the title track — the hero’s wondrous reaction to the brilliance of the Elysian sky after the Stygian blackness of the Underworld from Orfeo ed Euridice (1762) to Farnace’s rapt, and lengthy, ‘ Già dagli occhi il velo è tolto’ (‘Now the veil is removed from my eyes’), the villain’s moment of self-realization and remorse from Act 3 of Mozart’s Mitridate, rè di Ponto (1770).

Only eight yeams separate the mature, ‘Reformist’ Gluck’s celebrated arioso - although its rippling accompaniment derives from his earlier, pre-Reform Metastasian opera seria for Prague, Ezio (1750), in which the villainous emperor Valentiniano has a moment of introspection as he contemplates the beauty and restful quality of a babbling brook. It would have been interesting to hear that aria in this context, but Mehta ah Jacobs prefer two of the titular hero’s arias from the same opera, although the booklet does not make clear from which version these arias come — the 1750 Prague original or the radical revision for Vienna of 1763 , a year after the premiere of Orfeo. ‘Che puro ciel !’ turns out to be the only popular track in an otherwise recherché but vocally challenging and often musically fascinating programme.

Denis Morrier’s whistle-stop programme note credits Tommaso Traetta, as much as Gluck, with the reform movement in classical opera, citing his adaptations for the Francophile Bourbon court of Parma of texts originally set by Lully and Rameau, reconceiving them as Italian opera serie (Armida, Ippolito ed Aricia, I Tintaridi / Castor et Pollux). Mehta and Jacobs choose Emone’s fiery ‘Ah, se lo vedi piangere’ (‘Ah, if you should see him weep’) from Antigona (1772 , St Petersburg) , which Christophe Rousset recorded complete for Decca (reviewed in March 2001), but the track that really whets the appetite for a Traetta revival is the extraordinary scene in which the Furies torment Oreste with a vision of his murdered mother, Clytemnestra, from Ifigenia in Tauride (1763 , Vienna) , which Gluck himself conducted in Florence more than a decade before embarking on his own treatment of the same subject, his masterpiece Iphigénie en Tauride. The bold, dramatic choral writing (the choir here, and in the choral postlude to ‘Che puro ciel !’ is the excellent RIAS Kammerchor) clearly influenced Gluck and, through him, the Mozart of Idomeneo. Mehta is at his best here as the conflicted, tormented matricide.

He is also spectacular in the virtuoso arias, Arbace’s tempestuons ‘Vo solcando un mar crudele’ (‘I plough a cruel sea’) from the ‘London’ Bach’s Artaserse (1760), Ezio’s defiant ‘Se il fulmine sospendi’ (‘If you stay your thunderbolts’) — with its ‘military’ accompaniment of flutes, oboes, trumpets, horns and drums — and Orazio’s wide-ranging and chromatic ‘Dei di Roma, ah perdonate!’ (‘God of Rome, forgive me’) from Johann Adolf Hasse’s Il trionfo di Clelia (Vienna, 1762, the year of Orfeo and premiered in the same Burgtheater), which Mehta and Jacobs take at a breathtaking lick. I am slightly less taken with some of Mehta’s mannerisms, a tendency to ‘squeeze’ his tone for expressive effect, and a slightly wheedling timbre that sounds — to my ears at any rate — alien to Orfeo but might have worked for Valentiniano’s ‘blueprint’ aria from Ezio.

Despite this slight reservation, there is much to enjoy here and it is clear that a genuine musical spark ignites the rapport between conductor and singer, who, his biography in the booklet informs us, is following his mentor’s footsteps into a conducting career.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews