Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Bertil

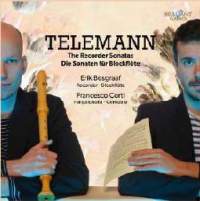

van Boer Music especially written for the recorder (sometimes called in the original sources flûte a bec) abounds in the huge oeuvre of Georg Philipp Telemann, who himself remarked on at least one occasion that he had taught himself to play the instrument when in his youth. There is room here, of course, for an invidious comparison with the legions of modern players or non-players who first tackled music through poorly designed and fabricated instruments, but during Telemann’s time to play a woodwind was an important aspect of one’s knowledge of orchestration. How proficient Telemann was is anyone’s guess, but his recorder parts, many of which are generically also written for transverse flute and/or violin, contain some highly virtuoso material that requires an equally high degree of technical skill. It may not be quite as tricky as Vivaldi’s sinuous parts, but nonetheless, Telemann demonstrated a real talent in knowing just what this soft instrument could do. It is therefore surprising that there doesn’t exist more than a handful of sonatas for the solo recorder and continuo, and even among these are a rather impressive number that contain alternative solo instruments. This disc purports to have included all that can reasonably be said to have been composed by Telemann specifically for the instrument, and it is not surprising that these mainly come from sets of published compendia meant for the general, but knowledgeable public: the Essercizii musici from the middle of the 1720s, Der getreue Musik-Mester from about 1728, and the Neue Sonatinen, two of which were advertised in 1731. Only one of the number exists in manuscript copy, but the rest were published as part of Telemann’s nod to public consumption of music. The notes claim that this represents an intimate side of Telemann’s oeuvre, something more personal. If so, the virtuosity that is represented in all of these sonatas must mean that the composer was a top-class virtuoso on the instrument. Despite the self-proclamation that he taught himself to play it at an early age, there is no evidence that he continued as a performer, and thus one must accept that, in his normal fashion, these works represent a thorough knowledge of what the recorder could do if in the hands of a professional. The pieces themselves are mostly in the normal four-movement pattern, though two sonatas only have three movements, and Telemann is careful to make the contrasts as wide as possible. For example, the F-Minor Sonata (TWV 41:f1) begins with a lovely, floating, and most intimate lament (marked Triste), but this is followed by a flashy and ebullient set of movements. The fourth movement of the C-Major Sonata (TWV 41:C2) twirls about in mad abandon with a solo line that runs all over the instrument’s range. A more sedate gigue can be round in final movement of the F-Major Sonata (TWV 41:F2), though the composer takes the instrument to the very top of its range at the end of the sequential phrases. There is more than a little bit of folk rhythm to be found. For example, the Gigue of the F-Minor Sonata (TWV 41:f2) contains an alla polacca, while the second movement of the A-Minor (TWV 41:a4) likewise is a polonaise with a vibrant rhythmic core. Even the second slow movement of the C-Minor (TWV 41:c2), in which the theme doubles round about itself like horses on a musical carousel, reflects the Polish style, and the final movement of the C-Major Sonata (TWV 41:C5) has a jaunty theme that sounds to my ears like a hornpipe. The first Allegro of the F-Minor Sonata (TWV 41:f2) is seamless, with no rests whatsoever. This impossible passage must require circular breathing, for the challenging virtuosity proceeds from beginning to end without cease. In terms of the performance, recorder player Erik Bosgraaf is utterly superb, with a clear tone and dexterity that has to be heard to be believed. Many of the fast passages are taken at a speed that is astounding, and yet not a note is out of place. Moreover, he even adds some improvised ornamentation on occasion, which makes incredible passage work even more delightful. He doesn’t drop the phrasing, which makes each and every sequence clear, and in the slower movements elicits some beautiful lyricism. According to the normal Baroque practice, there ought to have been a cello as part of the continuo group, but harpsichordist Francesco Corti’s deft and equally virtuoso playing makes this unnecessary in terms of the sound. It is as if both performers were completely and utterly in tune with each other in terms of style and nuance. And the virtuosity of Bosgraaf in the scurrying sequences at tempos that would make normal performers quail comes through clearly. This is precisely the sort of recording that one needs to have in one’s collection, as it will clearly knock your socks off. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|