Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

||||

|

Reviewer: Michael

De Sapio

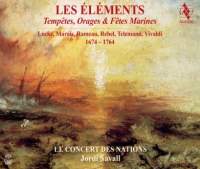

If you were under the

impression that tone painting started with the Romantics, this pair of discs

(taken from a live performance at a music festival in Narbonne, France) will

prove you wrong. This program of musical “tempests, storms, and marine

festivals” from the 17th and early 18th centuries shows that composers of

that era were keenly interested in the pictorial capabilities of music and

its power to move and astound the listener by evoking the wonders of nature.

Rebel’s suite Les éléments, which opens the program, has the most copious

descriptive content. To depict “Le cahos” (chaos), Rebel starts off with a

dissonant tone cluster that seems to take us out of the Baroque and straight

into the era of Ives and Stravinsky. The music soon settles into

18th-century practice, though, and there follow imaginative movements

depicting water, air (complete with avian sounds), earth, and fire, along

with some typical French dances.

As for the rest of the

program, storm movements from operas by Marais and Rameau and especially

Locke’s incidental music from The Tempest are all of strong musical

interest. Less so Vivaldi’s “Tempesta di mare” Recorder Concerto, a tepid

piece which fails to sound much like its purported subject (a storm at sea),

and Telemann’s rather facile mythology-inspired Wassermusik suite; yet they

too help fill out our picture of program music in the Baroque.

Le Concert des Nations makes

an impressive showing at the start of the Rebel, with an intensely raw sound

in “Le cahos” and some fearless unison playing from the violins in the

furious figurations depicting “Le feu” (fire). With whooping natural brass

and slashing strings, even the non-programmatic Loure is made to sound

pictorial. But problems start to creep in with the Sicillienne, where the

slack ensemble seems to go beyond a mere interpretation of the “lazy” French

style. Locke’s Tempest music, with its eccentrically cranky lines and

convoluted textures (part of Locke’s distinctive personal idiom), gives rise

to some distressing ensemble problems. The evocative “Curtain Tune”—the only

programmatic movement in the suite, depicting a rising and subsiding sea

storm—sounds “at sea” indeed; one searches in vain for a clear pulse in the

slow parts. In the dances, lines seem to collide and crash; many movements

end with a type of exaggerated ritard that might be described as “stumbling

to the finishing line,” a clear sign of ensemble instability. All this is

puzzling, since Jordi Savall is listed as the director, and photos included

in the booklet show him conducting the ensemble; but at times Le Concert des

Nations sounds here like a conductorless group, one in which the various

sections of the orchestra are unable to hear each other well. Perhaps the

stage setup was to blame.

In addition to interpolated

tambourine in several of the dance movements—sometimes a bit

overenthusiastic, though mostly tasteful—we also hear intermittent

theatrical sound effects by a wind machine. This may well have been

effective in performance, but on a recording it soon becomes hokey and

tiresome. Recorded sound is good; the audience is quiet, and the only

applause that has been included is that at the very end. The audience also

seems to be participating in the final Rameau Tambourin, with some clapping

in rhythm! Finally, we may question the appropriateness of the ecological sermonette which Savall integrates into his program notes, an earnest attempt to tie Baroque nature music in with the modern “climate change” movement. Mixing politics with music is never a good thing; nor are the philosophical underpinnings of Savall’s preachments very apropos to a concert of period music. Would it ever have occurred to Rebel or Telemann—men of a Christian age with a Christian cosmology—to personalize the planet Earth to the extent of describing it as the “victim of aggression” whose “principal enemy is Man”? In sum, an exciting concept, but the end result is less than recommendable. | ||||

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

||||