Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

Fanfare Magazine: 37:4 (03-04/2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Les abonnés à Fanfare Magazine ont accès aux archives du

magazine sur internet.

Subscribers to Fanfare Magazine have access to the archives of the magazine

on the net.

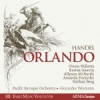

Atma

ACD22678,

Code-barres / Barcode: 0722056267823 (ID376)

Consultez toutes les évaluations recensées pour ce cd

~~~~ Reach all the evaluations located for this CD

In 1733 George Frédéric Handel was facing a rather difficult situation. He had managed to salvage a contract to produce Italian opera seria at the King’s Theatre when his own company became insolvent, but this didn’t mean that he was out of the financial woods. The lowbrow entertainment that drove his company into bankruptcy, the ballad opera, was continuing to attract audiences, and what is more, a rival company had been formed with the intention of sweeping up whatever crumbs were leftover in terms of serious opera. It was not, as they say, a fortuitous moment for the composer. It required works that were novel, music that was incomparable, and a subject matter that was both unusual and perhaps even a bit exotic. For Handel, of course, this was hardly a real challenge, and in the space of a year he produced two works which can be seen as some of his best, this opera and Alcina.

Orlando was borrowed from an Italian text originally set by Domenico Scarlatti two decades earlier, the plot of which was taken from Orlando furioso, Ariosti’s rather substantial fiction of the Christian-Muslem wars during the reign of Charlemagne. Orlando, of course, has a perennial problem with anger management, and he is not so hot on rejection, either. He thinks he has a love interest in the Chinese princess Angelica, who he has rescued from a fate worse than death (and which doesn’t come into the plot here). She, however, loves Medoro, a wounded Saracen warrior (the actual global distance between Cathay and Iberia being ignored). He is being taken care of by Dorinda, a shepherdess (and extremely naïve). Into this mix comes Zoroastro, who acts sort of as a counselor-mediator between all concerned. What is more, he is a magician to boot, so he has, as they say, “powers” at his command in case his logic doesn’t work.

In the first act, Orlando sets out to prove his love for Angelica, despite the fact that she tries to tell him that there is someone else. Medoro flirts with Dorinda, and at the end finally disillusions her of any further dalliance, much to her dismay. By act II he has discovered that Angelica has been leading him on and, understandably, goes completely berserk, imagining himself thrown into Hades. Zoroastro prevents mayhem by arriving in a chariot drawn by dragons (with a nod of course to Medea) and whisks him away. Finally, in the third act, Angelica decides to leave her Sylvan dell and return to China. Dorinda arrives and tells her that Orlando has finally caught up with Medoro and killed him. When he arrives, she rejects him once more, whereupon he picks her up and heaves her down into some sort of cavern-like well. Thereafter, he tries to leave, presumably to continue madly attacking people in a psychotic manner. Zoroastro arrives, arranges for a potion to be delivered by a couple of cherubs, makes Orlando drink it, and not only does this restore his wits, but he promptly forgets he was ever in love, and both Angelica and Medoro reappear magically from out of the cave. At the end, Dorinda, the only one who seems not to have gotten anything out of this, throws a party at her place to celebrate the triumph of love.

As an opera seria, at least it doesn’t have anything to do with Greek or Roman gods or heroes, but even audiences of the time would not have found the plot especially entrancing. No matter, since for Handel it was enough to have something vaguely exotic into which he could pour his musical muse, and this text suited admirably.

The entire opera is, as one might expect, filled with one great tune after another. Handel knows how to integrate accompagnato, recitative, and aria, even as he adheres to the traditions of the opera seria. Dorinda’s lovely, lilting “Quando spieghi” in the second act has a pastorale purity in the rocking compound meter motion, while Orlando’s bravura “Fammi combaterre” in the first weaves an intricate and forcefully virtuosic line as the knight threatens to take on all comers for Angelica’s love. The trio “Consolati, o bella” has each of the characters playing off each other, with solo spots against a duo as Angelica and Medoro try to console Dorinda. Orlando’s “Stigie larve” begins with a mysteriously mincing accompagnato, followed by two successive arias, the second of which (“Vaghe pupille, non piagete”) moves in a slow, solemn lament, as if the words are belied by the mournful music. The finale (“Oggi trionfo”) is almost a vaudeville, with each character in turn moralizing, but with a rather noisy accompaniment, as if to say to the audience that the entire two-and-a-half hour musical festival is about to end. By this stage no one cares whether the deus ex machina makes sense at all.

What really brings this work to life, of course, is the performance. The Pacific Baroque Orchestra is at the core, and conductor Alexander Weimann keeps his troops moving along with tempos that are more akin to the text. The Largos are not too slow, the Allegros not played Prestissimo, and this allows for all of Handel’s subtleties to emerge. This is particularly effective in the introductions, and in some instances, notably the opening monologue of Zoroastro, the chorale-like walk foreshadows the two armed men in Mozart’s Magic Flute to my ears (though of course musically different, but the mood is similar). The addition of a discrete horn adds emphasis without punctuating the text. Owen Willetts has a nicely resonant voice, and he takes on Orlando’s schizophrenic moods and tempos with ease. Soprano Karina Gauvin is suitable heroic, with an equally resonant tone, while Amanda Forsythe’s lighter voice is perfect for the jilted shepherdess Dorinado, portraying musical innocence with no fault. Allyson McHardy’s Medoro is rich and expressive, and Nathan Berg’s bass is truly stentorian. In short, this is an outstanding recording, and I suspect that it may even make my Want List for the year. Orlando has been recorded by the period performance “best,” including Christopher Hogwood and William Christie. This, however, is the one I shall keep.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews