Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

GRAMOPHONE (03 /2014)

Pour s'abonner /

Subscription information

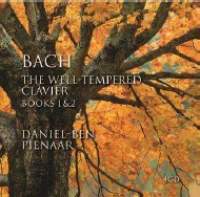

Avie

AVIE2299

Code-barres / Barcode : 0822252229929

Reviewer: Philip KennicottFermer la fenêtre/Close window

A simultaneous evaluation:

JS Bach Das wohltemperirte Clavier – Book 2, BWV870-893 Christophe Rousset hpd Aparté M b AP070 (157’ • DDD)

JS Bach Das wohltemperirte Clavier, BWV846-893 Daniel-Ben Pienaar pf Avie B d AV2299 (3h 38’ • DDD)

After complete cycles of the Mozart and Schubert sonatas and an account of the Goldberg Variations, Daniel-Ben Pienaar continues his ambitious pursuit of the whole, this time with a four-disc complete recording of both books of Bach’s WellTempered Clavier. This is his second recording of the first book, now paired with a previously unreleased traversal of Book 2. It arrived hot on the heels of harpsichordist Christophe Rousset’s release of Book 2. After recording the bulk of Bach’s keyboard literature, Rousset jumps into the WTC seemingly from the back end, leaving the better-known and in many ways more manageable Book 1 presumably for later. But that is slightly misleading: the heft of Book 2, its greater musical complexity, deeper intellectual challenges and more hermetic beauties make it a logical starting point for someone who has already left distinguished recordings of the Goldbergs, Partitas, Italian Concerto, French Overture and suite cycles, as well as the concerto repertoire.

These two releases set up an accidental dialogue, and perhaps it isn’t fair to either artist to pursue it too far. At this point in the evolution of period style and performance, the harpsichord is simply a different instrument – different capacities, avenues of expression and demands on the listener. Pienaar’s Bach is as pianistic as Rousset’s is of the clavecin, the former smooth and flowing, the later a study in articulation, small agogic details and a thousand shades of ornament.

Take, for example, the G minor Prelude and Fugue from Book 2. Pienaar’s doubledotted rhythms are expressive gestures, and give one a sense of seriousness and even grandeur, while Rousset’s rendering is crisper and more consistent, and fundamentally embedded in the rhythmic DNA of this essentially French style. Pienaar plays with the basic pulse, allowing little expansions and contractions, and even a rather daring (and I think not entirely successful) relaxing of the tension several measures before the end of the prelude. Rousset keeps it steady, drawing interest and expressive power from the tension between the sustained moving lines, and exploiting the pure drama of his instrument’s resonance as the music touches on and quickly resolves delicious moments of dissonance. Rousset’s harpsichord, a 1628 Ruckers ravelement, is an equal collaborator (enjoy in particular its bell-like sonorities in G major or the slightly astringent sound of the theme in the F sharp minor fugue).

Tempi in the G minor fugue vary considerably too. Pienaar particularly enjoys the more relentless of the fugues, including this one, which, after a series of broken but emphatic statements, breaks into a long, fluent sequence of semiquavers, an idea that builds through the fugue to an almost organ-like density. His reading is fast and urgent, with more attention to the colour and drama than to the individual voices. Rousset takes this slower, more alert to contrapuntal detail, and in the end, more powerful in its cumulative impact.

For listeners without strong loyalties to either the piano or the harpsichord, Rousset’s recording will be preferred. He is one of the finest harpsichordists working today and these readings, while never pedantic or ponderous, feel fully studied and assimilated. The harpsichord, by its nature, is a more intimate instrument and demands a more intimate kind of listening, and Rousset rewards that attention with myriad small refinements. Pienaar’s WTC is impressive and full of lively ideas. But it also arrives not so long after pianist András Schiff’s exemplary account of both books. If two recordings were to be juxtaposed, to show each instrument at its greatest potential in this repertoire, it would make sense to acquire and savour both Schiff and Rousset.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews