Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

|

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Jed Distler

Very popular was the ‘London Bach’, his combination of stile galant and Italian forms zestfully received. Four years after arriving in 1762 he produced the Op 5 Sonatas for the Pianoforte (fortepiano? square piano?) or Harpsichord. But Bach, ‘who observed the law of contrast as a principle’ (Charles Burney), even extending the Alberti bass pattern to the treble, probably preferred the newer instrument.

Bart van Oort doesn’t make much of its inherent possibilities in the first four sonatas. Dynamics, always forte or piano with a single crescendo (in the Tempo di minuetto of No 1), are played down – notably so in the second movement of No 3, a theme and variations marked Allegretto. Van Oort glosses over the very rapid swings from loud to soft in the second part of the theme and at his chosen tempo garbles the semiquaver triplets in Vars 3 and 4. Repeats aren’t always logical either.

Paradoxically, van Oort is comfortable with the absence of any dynamics in the last two sonatas. And options are artistically chosen, scintillating rather than aggressively inflexible in the opening Allegro assai and closing Prestissimo of No 5, the moderator used in the Adagio to enhance an expressively undulating line, an invitation for a cadenza at the third fermata accepted. Shades of Empfindsamkeit probably inherited from CPE Bach are heard too, markedly so in No 6, the most substantial of the set (all three movements are in C minor, a striking fugue in the middle preceded by another invited cadenza) and eliciting the finest interpretation. Nalen Anthoni

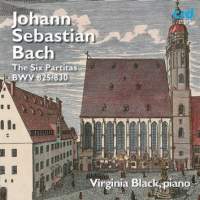

Although Virginia Black is a leading harpsichordist, she now goes back to her roots by recording Bach’s Six Partitas on a modern concert grand. In essence, she sounds like a seasoned harpsichordist playing the piano, not unlike one who speaks a foreign language clearly and fluently, yet not idiomatically, and with a noticeable accent.

As a result, characteristics of Black’s harpsichord technique get lost in translation. For example, her use of finger legato and agogic stresses in the First Partita’s Praeludium and Gigue does not tap into the piano’s capacity to articulate sustained and detached phrases through dynamics and tone colour. In faster movements featuring busy ambidextrous contrapuntal intricacy, Black tends to focus on the right hand while playing left-hand lines on top of the keys, without comparable firmness or direction, as in the D major Gigue, C minor Rondeau, A minor Fantasia and G major Praeambulum. In the A minor Corrente, long rapid lines do not consistently conclude with their initial energy and specificity, not unlike a person speaking to you who looks away just before finishing a sentence.

However, Black’s intimate style sometimes yields arresting results. I find her terse introduction to the E minor Partita’s opening Toccata refreshing in its lack of rhetorical grandiosity, as well as the headlong, no-nonsense treatment of the middle section. The Gavotta, by contrast, is lilting, relaxed and gorgeously inflected. And for more successful equanimity between hands, listen to the A minor Allemande’s carefully sculpted lines, which unfold with a sense of air between the notes. I have no doubt that the more comfortable Black becomes in the piano’s skin, the more her deep-rooted harpsichord experience will enhance her Baroque piano interpretations. She’d be dynamite in Rameau.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|