Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

|

|

|

Reviewer: J.

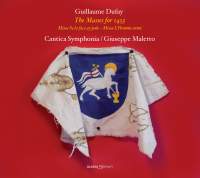

F. Weber Giuseppe Maletto has devoted a fair amount of attention to Guillaume Dufay (1397–1474) in recent years, but his only previous Masses were the first and last of his works in this genre (Fanfare 30:3), made for another label some years earlier than the reissue reviewed there. This time he pairs two middle-period Masses that he classifies as “for the year 1453.” One work may be slightly earlier, the other decidedly later, but the year remains significant. The most recent recording of Missa Se la face ay pale was by Andrew Kirkman (32:5), where a list of the 11 earlier versions was given. (As it happens, no recording of any Dufay Mass has appeared since then.) This Mass has been widely regarded as a wedding Mass, perhaps composed for the wedding in 1452 of the future Duke Amadeus IX of Savoy and Yolande, the sister of the future Louis XI of France. But in a brilliant new interpretation, Anne Walters Robertson, writing in The Journal of Musicology in 2010, connected the Mass with the House of Savoy’s acquisition of the Shroud of Turin in 1453, interpreting the “face” of the theme as the face of Christ. The other Mass is certainly later; according to Craig Wright, who has studied the whole broad matter in depth in The Maze and the Warrior (Harvard, 2001), “Sometime during the late 1450s or early 1460s—we can’t be precisely sure when—Guillaume Dufay wrote the first polyphonic Mass incorporating the Armed Man tune” (p. 175). The review of the Missa L’homme armé by Busnois (26:2) listed all the recordings of this group of Masses, although several additions to the list have been made since then. But the Mass is connected with 1453 by the fall of Constantinople that year, the provocation for the crusading zeal that centered around the Armed Man among the Knights of the Golden Fleece. This pair of Masses falls in the middle of the composer’s creative work. The Missa sine nomine (reviewed under Collections below) and the Missa Sancti Jacobi belong to the 1420s; the Missa Puisque je vis (27:2), preserved in Sistine Codex 14, dates to the composer’s presence in Rome between 1428 and 1437, if it is indeed his work, and the Missa Sancti Antonii de Padua (19:6) can be dated to 1450. The two late Marian Masses can be placed in the 1470s, adding speculatively as another late work the Missa Sancti Antonii Viennensis (from Trent Codex 89, edited by Planchart). Robertson writes the notes on the music, while Maletto writes on the performance practice, his use of instruments (organ, harp, fiddles, trombones) in both Masses. He concedes that Dufay spent many years in two places—the Sistine Chapel and the Cambrai Cathedral—that used no instruments at all, yet he still finds arguments for using them here. In the review of Kirkman’s recording cited above, it was noted that the trend has been sharply away from instruments and, less definitely, away from choral forces in that Mass. I find Maletto’s instruments a little more intrusive than I would like, and the a cappella versions (Kirkman and the Hilliards for Se la face ay pale, Summerly and the old Hilliards for L’homme armé) are much to be preferred. But Maletto makes a strong case for his approach. His seven mixed voices (only five in L’homme armé) make up a fine ensemble, as we heard in his several earlier Dufay programs. Definitely worth hearing for comparison. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|