Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Huntley

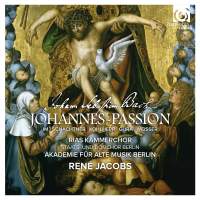

Dent So many unanswered questions swirl around Bach and authentic style that you can either tear your hair out in frustration or look upon the lack of definitive answers as open season. René Jacobs has made his name by taking the second option, and he doesn’t change tack here. He applies his talent for originality to give the St. John Passion as much immediacy as possible. Jesus treads the boards without running away from Bach’s church setting. Musically Jacobs has made some decisions, as we’d expect, that no one else, in my experience, has made. In every case, his choices bear fruit, making this new release a contender for top choice, and not just among period performance devotees. The logistics of chorus and soloists are flexible, echoing what Bach might have done but not feeling restricted to historical guesswork. The solo quartet is merged with a small choir of 16 members for the choruses, which is then amplified to a larger chorus and boys’ choir for the chorales. This gives the impression of a community of worshippers joining in the liturgy. The choruses gain theatricality, moreover, since some verses are sung by the solo quartet alone. Even when they aren’t alone, their individual voices stand out. The effect is quite striking, as one immediately hears in the great opening chorus, “Herr, unser Herrscher,” where Jacobs, like Nikolaus Harnoncourt decades earlier, asks for wrenching, even raw singing: We are hearing a cry from the souls of sinners. No one knows, or reasonably can guess, how much emotional expression Bach expected of his singers, and current HIP fashion, which is to sound as “white” and antiseptic as possible, leaves me cold. So I am a rapt listener to Jacobs’s approach, just as I am for his liberal use of crescendos to create climaxes in the chorus. The chorales give an overwhelming sense of the affirmation of faith. Accordingly, the instrumental playing from the adept Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin is warm and smooth, again defying the period performance standard of spiky attacks, hairpin dynamics, and emotional neutrality. The continuo for the recitatives is varied, the richest being associated with the Evangelist: lute, organ, harpsichord, viola da gamba, cello, and bass. That’s quite a company, but their blended sound is smooth and not overly dominant. There’s also an elaborate spatial positioning of the orchestra, chorus, and soloists, with the dramatis personae stepping forward out of the chorus for their parts. Little of this is very evident in the soundstage, at least as heard in a download. (In physical form you get two SACDs, along with a bonus DVD that I didn’t see.) Because he’s situated separately, the Evangelist of Werner Güra isn’t the tenor in the solo quartet or the tenor arias (but we get Johannes Weisser doing double duty as both Jesus and the soloist in the bass arias). My most recent encounter with a superb Evangelist was Mark Padmore last year in the Berlin Philharmonic’s high-profile staging of the St. John Passion by Peter Sellars on video (reviewed in Fanfare 38:4). Güra, for whom I have great admiration, is just as moving, dramatic, and artistic, but he has a fresher voice. That Berlin production features a superior Jesus in Roderick Williams, with the bass arias undertaken by Christian Gerhaher. By comparison Weisser lacks a lustrous reputation and wide recognition, but he was superb as Jacobs’s Don Giovanni. He’s equally fine here, adding a strong note of dramatic authority to his portrayal of Christ instead of the usual resigned pathos. The other soloists, including a male alto, rank high among period singers, although I won’t surrender my preference for the great voices who used to populate Bach recordings in the 1950s and 60s—there’s no Fritz Wunderlich or Kathleen Ferrier in the lineup. Never known as a respecter of authority, Jacbos doesn’t bow to HIP orthodoxy, either. His tempos are urgent but not recklessly fast, and he doesn’t create false excitement through tempo, even though the aim here is clearly to be exciting. We are drawn into a tragedy happening in the moment, before our very eyes. Even with the advantage of characters moving in and around the stage, the Sellars production feels both morose and slow in comparison. I’m also grateful that Jacobs has had the good sense to realize that the St. John Passion is a worshipful work first and foremost—how did we ever reach the state where this needed arguing? He leads the score as if God matters. As to the text, Bach worked on the St. John Passion from its premiere on Good Friday 1724 in Leipzig until 1750, near the time of his death. The detailed and knowledgeable program notes suggest that he wasn’t trying to improve an imperfect work over this long time span but instead rethought its style and aims each time the work was performed. In place of an Urtext, we face something like an archeological site with multiple layers to be dug through. As changes occurred to the composer, various manuscripts and copyists’ parts were saved or discarded. The parts that did not change over the entire 26 years (primarily the complete continuo from 1724, which provides the architecture for the entire work) form the foundation of the archeological dig, so the program annotator argues. As a listener with no particular bias about the world of Bach musicology, I can’t enter into the thickets of dispute and conjecture. “Our” St. John Passion, adopted since early Victorian times, consists of a manuscript Bach commissioned from his copyist in 1749, but it’s not a version he ever heard. The first 10 numbers don’t even contain revisions he added up to 1739, the year, we are told, he apparently lost interest in writing Passions. Jacobs follows convention by using the final source with the addition of movements from 1725 that have become mandatory for their musical beauty even though Bach subsequently removed them. My apologies if I’ve overlooked some niceties that will leap out at Bach specialists. As much as anyone I dread the steel jaws of rabid scholars snapping shut. I’m torn over summarizing Jacobs’s own lengthy justification for the choices he has made for this recording, since they wade hip-deep into the one-to-a-part controversy (he’s against it, calling the reduction of the singers to only four “Bach’s nightmare”) and much else. Even the definition of “choir” is worked over; Jacobs contends that the word was broader in Bach’s usage and constitutes both the chorus and the instrumentalists. Not surprisingly, he isn’t interested in reconstructing an authentic count of performers so much as reviving the dramatic intensity of Bach’s “vocal ‘concerto principle’”—the mixture of a solo quartet and the larger force they are embedded in. Jacobs is witty enough to justify the full strength of 36 chorus members in the chorales by saying that “God and also Bach, who composed for the glory of God, would have been very reluctant to exclude [them].” Clearly Jacobs isn’t the first conductor to know what he wants and then props up his vision with a sprinkle of musicology. What sets his reading apart is its theatrical impact and the revival of reverence for the score’s biblical sources. No finer version of the St. John Passion has come my way in decades. | |

|

Support us financially by purchasing this disc from eiher one of these

suppliers.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|