Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Bertil

van Boer

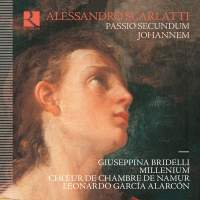

Among the earliest

compositions of Alessandro Scarlatti are those probably written either in

Palermo, his home town, or for the oratory of Santissimo Crocefisso in Rome,

the same venue as hosted the oratorios of the popular Giacomo Carissimi.

This work, however, may have been among those composed by the 25-year-old

composer for his new home in Naples, as recent research has disclosed. He

had arrived there to write operas for the San Bartolomeo theater two years

earlier, having already established himself in 1679 with the opera Gli

equivoci. Of course, politics was very much in the air, and there was

considerable maneuvering before Scarlatti was appointed as maestro di

cappella for the Neapolitan viceroy. As the young buck on the block, the

composer set about establishing himself both at the opera house and writing

music for the court. Given the needs for sacred music, Scarlatti also began

to delve into that realm, in effect merging the styles so that both the

stage and altar were interchangeable musically.

This Passion was probably the

result of his new appointment, though it seems to have been a parallel work

with a Passion by his colleague Gaetano Veneziano (1656–1716). There seems

to have been some considerable affinity between the works, but Scarlatti’s

version is much more succinct and focused, less rambling or ornate. It is as

if he were trying to impress his patrons with something less ostentatious,

but it could also have been due to either tradition or his own youthfulness.

Whatever the reason, the Passion is quite short, and to fill out the time,

conductor Leonardo Alarcón has inserted the responsories for Settiman Santa,

likewise by Scarlatti. The pairing of these two works has resulted in a nice

continuity of music, though the latter may date from a decade and a half

later.

The opening chorus of the

responsory is a vernacular Stabat Mater, with a close set of suspensions and

dissonances, a lament that is moving and heartfelt, slowly unfolding with

glimpses of a major key, but the entire chorus, repeated partially after the

initial movement of the Passion, flows in a languid, yet mournful stream. In

the next section drawn from this work, the Ecce vidimus, an opening leap of

a fifth seems musically surprising, but the remainder is likewise slow and

moves in parallel with only the usual close suspensions. The same mood

persists in the Omnes amici mei, with a slowly descending line that suddenly

and without warning erupts into a fast phrase that vanishes as quickly as it

appears. The fruit of bitterness is solemn and chorale-like, while a similar

tone expressing deep sorrow with a static set of harmonies forms the O vos

omnes. The final responsory is the Aestimatus sum, where the feeling of

helplessness is complete with the lament, with imitative voices at the

beginning, including a very low and ponderous bass voice, as emerging or

descending into the pit. But the final flourish turns nicely to major,

expressing hope. As for the Passion itself, it is rather more kaleidoscopic. The narration by the Testo interrupts bits and pieces of chorus and solo responses as the text by John are read without commentary. Peter follows Christ, but when questioned denies his allegiance: The maid first questions him in a brief soprano phrases, interrupted by Peter’s denial that is no more than a note or two in length. The Testo’s narrative is often punctuated by ornamented lines, sounding for all the world like a page right out of Carissimi’s better-known oratorios. The arioso dialogue of Jesus, sung in a resonant bass by Salvo Vitale, flows gently and distinctly, with a violin accompaniment often providing counterpoint. Pilate’s questioning is answered by a dance-like tune in the chorus (Turbae), but the entire dialogue flows in a continuum. As for the recording itself, Giuseppina Bridelli’s Testo is suitable fluid and expressive, with clear and unambiguous diction. As noted, Vitale’s Christ is marked by a deep and virile tone, while Pierre Derhet’s Peter is suitably pointed and succinct. The intonation is excellent, and the Millenium Orchestra is discrete in their accompaniment, allowing for the story to clearly unfold. The choral work of the Namur Chamber Choir is also quite nuanced, with the often gnarly harmonies emerging in a continuous flow. While the mournful tone of both works might be a bit much for listening outside of the contemplative Easter season, the combination works quite well as both story and commentary. This is one disc that one ought to bring out at Lent for the proper mood. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|