Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Reviewer: Hugh

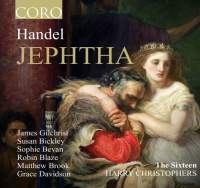

Canning Recordings of Jephtha have, sadly, never been numerous so any new version featuring a sasoned Handel choir and some of the best of today’s young Baroque stylists is more than welcome. Handel's last original oratorio ‑ that has to be qualified, of course, since recycling earlier music, usually with interest, was an essential part of the composer's creative process ‑ was completed with difficulty during the onset of the blindness that would end his active career after 1753. Yet, with Theodora (1750), Jephtha constitutes the summation of Handel's preoccupation with a genre he more or less invented: the English oratorio. When Haydn visited London 30 or more years after Handel's death he was still able to marvel at Handel's mastery of accompanied recitative, citing Jephtha's 'Deeper and deeper still', and his choral writing, which was to have a profound influence on Haydn's Creation and The Seasons on his return to Vienna. Like Theodora, Jephtha is one of Handel's most austere treatments of religions tragedy: here the Idomeneus‑like story of the Israelite leader who makes a fatal vow to sacrifice the first living creature he sees after victory in battle. In the Old Testament he fulfils his cruel unthinking vow, but in Handel's and Thomas Morrell's version, created on the cusp of the eighteenth‑century 'Enlightenment', Jephtha's daughter Iphis gets a partial reprieve. With our twenty‑first century moral view, we may be more amused than touched by the commuting of her sentence to perpetual virginity ‑ a fate worse than death to the modern world ‑ but Handel must surely have stirred and shaken his contemporaries with Jephtha's dilemma and the imagery of darkness and blindness that permeate the pages of Handel's score. He famously broke off writing at the Act 2 closing chorus, 'How dark, oh Lord, are thy decrees', writing in the margin, in his native language, 'Unable to continue because the sight of my left eye is so weakened.' This knowledge renders one of the bleakest passages of this valedictory score even more poignant and it is superbly sung by The Sixteen here. Harry Christophers has been gradually building an enviable back catalogue of Hndel oratorios on disc Som of the earlier issues, including Esther, Israel in Egypt and Samson, were initially released by the now defunct Collins Classic, but are no again generally available on Christophers’s ownlabel. More recently, he has added a fine Saul to the canon (I reviewed it in IRR in October 2012) and one hopes he will go on to add Theodora, Solomon, and possibly one of the secular 'oratorios', Semele or Hercules.

Like its predecessors, Neville Marriner's and John Eliot Gardiner's, this Jephtha offers an evenly balanced cast: James Gilchrist's titular hero is closer in timbre to the mellifluous Anthony Rolfe Johnson (Marriner) than to Nigel Robson's grizzled and gruff‑sounding but always dramatically compelling portrayal (Gardiner). If his sound is light, Gilchrist more than compensates with his trenchant diction and musical insights ‑ the accompagnato admired by Haydn, 'Deeper and deeper still', is a highlight not only of the oratorio but also of his performance. He suggests the military arrogance of this flawed general in 'Virtue my soul shall still embrace ‑ Goodness shall make me great', cockily proclaims, and yet he is profoundly moving at the moment of truth in an account of 'Waft her, Angels' that ranks with the best performances I have heard ‑his lissom tone weighed down with grief and love for the daughter he thinks he is about to lose. Handel just about redeerns Jephtha with this heart‑stoppingly beautiful aria, exquisitely sung here.

His daughter, Iphis, is sung here by the rising British star soprano Sophie Bevan in her most important recording to date. She rises to the challenge with ravishing tone in 'Tune the soft, melodious lute' ‑ a radiant persona, 'The smiling dawn of happy days' and a deeply touching sense of resignation in the almost unbearably wrenching 'Farewell ye limpid streams and flood'. This is an unforgettable performance which all Handelians will want to hear. Susan Bickley's Storgè seems to have cornered the market in the most recent live performances ‑ in concert and on stage ‑ of Jephtha I have heard so it is good to have her superb performance preserved here, as it is Robin Blaze's limpid, almost boyish Hamor and Matthew Brook's forthright, round‑toned Zebul ‑ an additional aria, adapted from Ptolemy's 'Domerò la sua fierezza' in Giulio Cesare, for the 1753 revival, is included as an appendix. The brigh‑eyed, upbeat Angel of Grace Davidson manages to make 'Pure, angelic virgin‑state shalt thoo live and ages late' sound like an invitation to a jolly party.

In sum, Christophers's considered view of Handel, devoid of extremes and eccentricities, and the work of his outstanding choir and orchestra make this a solid recommendation for anyone contemplating Jephtha for the first time, but even if you own Marriner and Gardiner this new version is a must‑hear for commnitted Handelians. The recorded, sound is vividly immediate and there is a readable and informative booklet note by Ruth Smith.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|