Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

Fanfare Magazine: 38:2 (11-12/2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Les abonnés à Fanfare Magazine ont accès aux archives du

magazine sur internet.

Subscribers to Fanfare Magazine have access to the archives of the magazine

on the net.

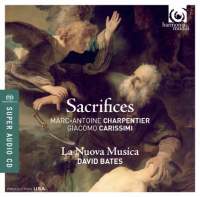

Harmonia Mundi

HMU807588

Code-barres / Barcode : 0093046758868

(ID468)

Consultez toutes les évaluations recensées pour ce cd

~~~~ Reach all the evaluations located for this CD

The ostensible theme of this album is its title, Sacrifices. Mercifully, that isn’t mentioned in the liner notes, as it only holds true for two out of the six included works. If there is any program here at all, it’s one of the passage of Italianate musical characteristics from Italy into France, from Carissimi to his pupil Charpentier, and the latter’s very personal achievement in les goûts réunis.

From the teacher, the student acquired recitatives with continuo, and a more melismatic, less syllabic approach to text setting than French musical culture traditionally supported. Both composers use highly varied musical textures, with an increased involvement of elaborate choruses, and a pair of violins performing what amounts to a separate vocal line. Charpentier also drank deeply from the wealth of expressiveness to be found in much Italian operatic music of the period. It is impossible to think of a French composer who could have written the chorus that concludes Le reniement de Saint Pierre, “Tunc respexit Jesus Petrum,” with its numerous false relationships, without awareness of contemporary Italian music. The liquid coolness that flows between its five parts brings to mind the Franco-Flemish heritage, but it is the Roman composers who gave Charpentier the tools to display his vivid theatrical sense.

All three dramatic motets are as operatic as one could wish, and not surprisingly so: They were part of Jesuitical attempts to halt and reverse the victories of the Reformation by personalizing the Bible through the arts. The people at the heart of each tale come to life with a vibrancy that Verdi wouldn’t scorn: the innocent joy, and subsequently, the chromatic anguish of Jephte’s daughter; the simple delight of Abraham and Isaac after the unnecessary torment they’ve been placed through has passed; the horror of St. Peter (as noted through choral narrator) after he realizes he’s indeed denied his God three times.

The three motets are separated by works written by Sebastien de Brossard, whose handwritten copy of Carissimi’s Jepthe is the one currently reposing in the Bibliothèque Nationale. (To complete the circle, he also referred to Charpentier as “the most profound and learned of modern musicians,” and hailed his Médee as the opera “of all operas.”) Brossard, who wrote the first French dictionary of musicians, amply demonstrated a cosmopolitan openness in his writings, but his own music is quintessentially French—none more so than his symphonies pur le Gradual for insertion in specific Masses by François Cosset and Bartholomeo Baldrati. James Anthony, in his French Baroque Music from Beaujoyeulx to Rameau, gives Brossard an offhand slap by passing over his trio sonatas with only the remark, “Of greater musical merit are the sonatas by Elisabeth Claude Jacquet de La Guerre,” but that’s really not fair. The one included on this album is a short work of delightful imagination, not to be compared for scope or variety with de La Guerre or Couperin, but no less worthy in its own right.

The performances are theatrical without ever venturing over the line into melodramatics. Singers for all parts are exceptionally well chosen, but I will single out for special praise Sophie Junker as Jepthe’s daughter. She has a narrow but attractive tone with a flicker vibrato—classically French, if one listens to historical recordings—that opens at the top into brilliance. In preference to deeper, richer voices, hers comes across as singularly youthful, making the heartbreak that comes of her father’s news all the more effective. Her excellent enunciation is mirrored in all the singers of La Nuova Musica, while the agility several display (including the unnamed bass who sings briefly as Filius Israel in Jepthe) is as fine as one could expect to hear from internationally renowned soloists. David Bates conducts with an ample sense of each moment’s drama, and his instrumental team performs as I noted in a review of Handel’s Il pastor fido, “with delicacy, energy, and charm.”

Full texts and translations provided, in Latin, French, English, and German. This release leads me to hope Bates and his musicians will record similar treasures by Carissimi and Charpentier, but in any case, this release is excellent.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews