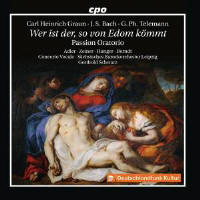

Reviewer: Bertil

van Boer

This entire oratorio is

something of a commonplace work in the 18th century, in that it represents

an adaptation or pasticcio cobbled together for a specific purpose; in this

case, a performance on Good Friday in Leipzig at the Thomaskirche in 1750.

Given that one of Johann Sebastian Bach’s duties there was to provide music

for the Passion, this work may even have been done somewhat earlier, and

certainly it was obtained by his son Carl Philipp Emanuel as part of the

musicalia left to him by his father. It seems to have been performed in

Hamburg, where C. P. E. also had the task, as did his godfather Georg

Philipp Telemann, of providing suitable music for Easter each year. In any

case, the bulk of the work is not by either composer, indicating that they

interpreted their duty in a rather more lax manner; suitable music did not

necessarily require a new composition, but could include various adaptations

as necessary.

What is known is that this oratorio began life about 1730 as Ein Lämmlein

geht by Carl Heinrich Graun, a work that was well regarded almost

immediately after its composition. Bach was certainly impressed by it enough

to purchase a copy for St. Thomas or himself. Since it was so well known,

however, Bach chose to alter the work so that Graun’s core was retained but

supplemented by new textual additions. Who did these is not known, though

Bach’s librettist Christian Friedrich Henrici (Picander) is the prime

suspect. This allowed for the music to be performed without public

attribution, not to mention for Bach to provide the additional material.

This comes in the form of a crib from Georg Philipp Telemann’s cantata Wer

ist der (giving the title to the oratorio as well) for the opening chorus,

and supplements in the form of a chorus and several chorales by Bach himself

(though they are largely anonymous in the sources). The result is sort of

super-Graun, a self-sustaining work that clothes an already popular oratorio

with selective new musical adornments suitable for the season.

Telemann’s opening chorus begins softly with a distinctive marching theme

against which the chorus enters selectively, all the time maintaining the

same pulsating march rhythms. When the bass solo comes in, the oboes swirl

about in a flowing stream that adds a layer of interest to the vocal line.

Thereafter the chorus and solo interact in the same fashion, with the tenor

solo in triplets above an ostinato unison string figuration. The style is

quite modern, reflecting the emerging Empfindsamkeit, of which Telemann was

one of the early adherents in his own compositional development. His chorale

that follows, however, is rather conventional. This blends perfectly with

the first part of the oratorio, which is entirely by Graun. His opening

chorus reflects the same steady marching rhythm as Telemann, but there is

more counterpoint and chromaticism. It is a bit more old-fashioned, but

nonetheless there are hints of the newer style, particularly in the

sometimes close harmonies. The first soprano aria, “Ihr Tropfen,” could be

right out of an Italian opera, with the violins dripping notes above the

steady and quite modern ostinato strings. The soprano line has some nice

coloratura, but it is not as effusive as his operas, being more sedate and

appropriate to the sacred style. The same modern feeling permeates the

second aria for alto, “Was an Strafen.” Here a pair of oboes provides the

musical foil for the clear lines of the voice with a short sequence that is

effective in portraying the mood. The tenor aria “Harte Marter,” may seem to

require a more furioso style, but Graun maintains the softer tone, here with

a pair of gentle flutes. Only in the soprano aria “Nimmst du die Kron” does

he insert a minor key that is moody and changeable in terms of emotion, and

yet does not fundamentally depart from the more reflective tenor of the

oratorio. The choruses that Graun inserts in places are all done in a like

manner, with commentary that supports the longer arias, such as the marching

rhythms and homophonic parallel vocal structure of “Er ist um unserer

Missetat.” The chorales that pop up now and again are perhaps the most

conventional of Graun’s music, as they are set simply enough so that the

congregation can sing along if it wishes.

Bach’s interventions are limited to the second part. As noted earlier,

almost all of them are various chorales that Bach either harmonized or took

from the normal hymns of the day. His opening chorus, however, was taken

from the Cantata, BWV 127, and while it reflects an older style, it seems

quite appropriate for this work. The swirling oboe and flute lines that

support the cantus firmus are typically Bach, and the interventions don’t

seem substantial. The bass arioso that follows has some affinities to one in

St. Matthew Passion, though it is not identical and its origins

cannot be determined, save that it is consistent with Bach’s style. He may

well have newly composed this piece. The oratorio then returns to the Graun

with a lilting duet, “Soll ich den von Jesu gehn.” Thereafter follows a

series of recitatives and arias by this composer, interspersed with the

various chorales. Of particular beauty with its lovely flute solos is the

tenor aria “Arme Seel, zerschlagenes Herz.” This would be a popular tune in

any of Graun’s operas, as it is sensitive and gentle. The “Schrecken” of the

tenor’s next aria is displayed by mournful solo bassoon above a halting

string accompaniment. It too is highly operatic. The Graun portion ends with

a thoroughly modern chorus with twirling flutes and no counterpoint.

There may be some differences between the Graun/Telemann portions and Bach’s

limited insertions, but the oratorio on its own seems remarkably cohesive.

Here one is reminded that Bach was no musical dinosaur, but rather kept

abreast of the times, even if he himself felt his own legacy would be passé.

If one is tempted to regard Bach as old-fashioned (even if a monumental

figure), this work and his gloss on Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater from the last

years of his life should provide the antidote. He was fully aware of the new

emerging styles, and when necessary adapted them to his own needs.

After such a long discussion, perhaps one ought to say a few words about the

performance. In a word, it is excellent. The Concerto Vocale is clear and

crisp in their diction, well-blended with the instruments, and adept at

Graun’s style of music. Conductor Gotthold Schwarz provides a good set of

tempos, indicating that he is thoroughly immersed in the music of this

period and the mood of this reflective oratorio. All four soloists likewise

have a good sense of pitch and phrasing. Passion oratorios may be a seasonal

thing, but this work and its excellent performance raises it beyond the

occasion, not to mention demonstrating how composers of this period were

able to merge their own styles and needs with others. Now, if only Ein

Lämmlein geht would be recorded on its own, but here this will amply

fill the bill until this happens.

Fermer la fenêtre/Close window |