Reviewer: James

V. Maiello

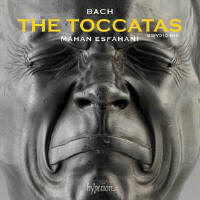

Bach wrote the Toccatas, BWV

910–916, in his early 20s, most likely while he was working at the ducal

court at Weimar. They reveal his engagement with the music of North German

composers like Buxtehude and Bruhns, as well as the young Bach’s identity as

a keyboardist, composing at the harpsichord or organ. At the end of his time

at Weimar, a more conceptual, abstract process would emerge as he

encountered Vivaldi’s music and matured as a composer. In the early 1700s,

though, Bach had a well-deserved reputation as a keyboard virtuoso, and one

of the attendant professional skills of any such musician was improvisation,

often in the form of toccatas and fantasias.

It is here that Esfahani falls short in his approach to these

works. To be clear, this is not a question of technique. He is a fine

harpsichordist, and he plays with exceptional control and precision. The

nature of a toccata, though, is one of extemporaneity, moving between

motives and thematic ideas with nonchalance and a certain impulsivity.

Esfahani takes a measured approach that makes Bach’s flourishes and

machinations sound stiff and contrived, though the playing is clean and

accurate. This might work well as a contrast to more improvisatory sections,

but not as a default approach, which tends to get too heavy and plodding.

This is particularly noticeable in the Toccata in C Minor, BWV 911, for

example: Esfahani’s stricter approach in imitative sections is spot-on, and

were it paired with a more flexible reading of the freer ones, it could be

revelatory. Likewise, the Toccata in G Minor, BWV 915, is too regulated for

me. It is full of opportunities to sound free and loose, but these are

controlled too tightly and do not provide enough contrast with the stricter

sections. Again, this is a difference of opinion about interpretation, not a

comment on Esfahani’s skills as a harpsichordist. Moreover, the instrument

itself sounds great, rich and clear, but with just a little bite; Hyperion’s

recording is clean and well balanced, as usual.

There is also the issue of the liner notes, a pseudo-scholarly ramble during

which Esfahani details his reasons for making his own editions from various

sources and outlines his process for doing so. Clearly, he is dissatisfied

with the performing editions available and seems to have a measure of

disdain for the musicologists who have edited them, though he does not

explain these grievances adequately or convincingly. Esfahani’s declaration

that he used “the old Bach-Gesellschaft printings as a template on

which [he] then notated the variants from each source” is problematic as an

editorial method for a number of reasons. Chief among them is that these

19th-century editions are universally acknowledged to be riddled with

errors, rendering them a wholly inappropriate model for comparison. Even if

all the variants are considered, starting from the BG, even if only for

convenience, this creates an implicit bias toward the BG as authoritative.

He might have been better to use the Neue Bach Ausgabe, which

contains much more reliable material for reference. Moreover, Esfahani’s

argument that “the musicological act is not one of establishing the textual

primacy of the sources but rather one of discovering the musical philosophy

behind the copying of those sources and the relation of that philosophy to

the physical act of playing and, more importantly, the artistic act of

interpreting” is nonsensical. The musicological aims he identifies are not

mutually exclusive, and one informs the other, or at least it should. Were

Esfahani so concerned about ability of musicology to affect interpretation,

he might have made something of Bach’s subtle allusions to dance styles or

emphasized the sectional contrasts so central to the musical aesthetics of

the period. At the very least, the performances should have reflected

improvisatory essence of the toccata as a genre.

In any

case, these are technically competent readings of the toccatas, but they are

too rigid and structured for my taste, and there are too many recent

recordings that take a more nuanced approach to Bach’s music for me to

recommend this recording. By way of example, both Stefano Innocenti

(Stradivarius, 2015) and Blandine Verlet (Decca, 2018) have released fine

recordings of these works recently, and DG reissued in 2013 Trevor Pinnock’s

landmark readings of the toccatas from the 1978 set.

Fermer la fenêtre/Close window

|