Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Ralph

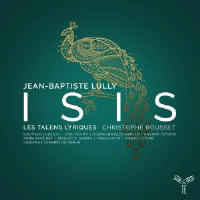

Locke In the past few decades music lovers have seen the near-death of studio-recorded opera. Most of the recordings of the standard repertory that reach us today—and many recordings of lesser-known works—were made at a staged performance or else “in concert” (that is, with the orchestra on stage and the singers standing in front, without sets and costumes and with minimal or no action). Recordings made before an audience are often more alive and dramatic, but the voices may be balanced louder than the orchestra (to limit rustling and coughing from the auditorium). Or perhaps a singer didn’t “prepare” a certain high note well. Some recordings try to get the best of both worlds by blending a performance with brief inserts from rehearsals or post-performance “patch sessions”. Studio recordings of Baroque operas, though, continue to be frequent, perhaps because the works involve far fewer performers (especially in the orchestra), so the sessions are simply less expensive. A sterling example of what can be achieved under modern studio conditions is this new, nearly complete recording of Lully’s Isis by Les Talens Lyriques.

Back in the 1960s and 70s, I didn’t believe what I read about Lully in the music-history books. He seemed a duffer to me. Now I know that the problem was the available recordings. The new Isis shows how artfully and sometimes powerfully Lully and his librettist Philippe Quinault could combine the existing elements of Italian opera (recitatives, short arias, and extended sung-and-danced divertisse-ments) to tell a story - in this case, two stories. Isis (Lully and Quinault’s fifth collaboration) combines two separate tales from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The basic plot involves Jupiter’s love affair with the nymph Io. His wife, Juno, is enraged. Juno in any work ends to be a great role, giving fine scope to a spitfire singer, usually a mezzo. Juno entraps Io and puts her under the watch of Argus, who has 100 eyes. But Mercury, determined to help Io escape, mounts an opera-within-the-opera in order to lull all 100 eyes to sleep. This lovely and powerful divertissement enacts the tale of Pan and Syrinx. It ends with Syrinx escaping Pan’s clutches by jumping into a riverbank and turning into a stand of reeds. Pan instantly feels her sorrow and his own and plucks some reeds so nearby shepherds can play on them as he sings a touching lament. The wind instruments are also understood as representing the moaning of Syrinx as the breeze sets the tall green plants into sonorous vibration. Two other vividly realized scenes (both in Act 4) involve Io being tortured, again at Juno’s command. Io is sent first to a frigid land (Scythia, found near the Black Sea) and then to a scorchingly hot smelting room where giants are hammering molten iron. In the first, the chorus and strings shiver in quick repeated notes; in the latter, the chorus engages in onomatopoeia, tapping the metal to the repeated syllable “tot, tot, tot” (translated in the booklet as “clang, clang, clang”). The opera ends with Jupiter promising Juno that his affections will no longer wander, and the couple allow Io to ascend to heaven and be worshiped by “the peoples of Egypt” under her new name: Isis. Thus, Isis—the title character—does not appear in the opera (except perhaps in the very final moments), and certainly never sings. In the header I have listed the six strongest cast members. They are an astonishing crew, singing with firm and beautiful tone but also acting and emoting through the voice. They employ all kinds of subtle technical devices, such as messa di voce (a crescendo or diminuendo on a single note) and artful applications of portamento. Two other singers are also heard a lot but are woofier (baritones Philippe Estephe and Aimery Lefevre). Many of the singers perform more than one role. There was historical precedent for this: the bass who played Jupiter in the premiere production at court added the role of Hierax as well when the opera was transferred to the Paris Opera, which performed for the public at the Palais Royal in the center of Paris. (Hierax loves Io. She once promised to marry him but, at the beginning of the opera, has begun to put him off because Jupiter is courting her.) There is much more doubling in this recording: if one counts roles in the prologue and in the opera, one of the singers takes 5 roles, another 8. In the case of Cyril Auvity (who does 5), I can hardly complain—he is one of the most beautiful lyric tenors I have heard recently, and also is capable of rising to great passion as needed. Still, this reappearance of the same singing voice in several roles made it hard for me to follow the action without constant reference to the libretto.

Christophe Rousset takes plentiful opportunities to enrich the somewhat skeletal score with varied sonorities. The continuo group consists of 5 musicians (including Rousset at the harpsichord) playing 7 instruments. In Pan’s lament for Syrinx, the flutists use recorders, and the keyboard continuo instrument is suddenly the organ; all of this adds the breathy sound of various “pipes” to this touching and disturbing number. Tempos always feel just right, and Rousset allows the singers the freedom to color their words with slight portamentos, sudden shifts of volume, and so on. I really felt that I was hearing individuals converse. It helps that most of the cast members are native French-speakers.

My one slight disappointment was in the “frozen North” scene. The opening chorus exists in recordings by groups that make it sound more like actual shivering. William Christie’s distressed-sounding singers recorded some excerpts from the work. Rousset’s chorus is admirably light and precise, but sounds very stylized in this passage, as if it were doing quick repeated notes in a minimalist piece from our own day. (That’s an interesting parallel, of course. Richard Taruskin has posited that Historical Performance Practice in a given era is often influenced by contemporary musical trends, such as Stravinskyan neoclassicism in the 1950s.)

The sound is superb, reminding us of the marvels that can be achieved by first-rate musicians working under studio conditions for three days. The work as a whole has been recorded once before, under Hugo Reyne (Accord, on 3 CDs and thus perhaps complete). That would have to be quite amazing to surpass what Rousset and his impressive crew have now achieved. Like the monophonic Callas/De Sabata Tosca and other operas from the great days of studio recording, Rousset’s Isis will be considered a classic for decades to come. Detailed synopsis, informative essay, and libretto, all presented in French and clear English.

| |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|