Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

|

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer:

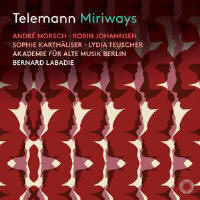

Richard Lawrence In all but name, Miriways is a German-language opera seria, with a happy ending after the characters have confronted – not too seriously, admittedly – the problem of love versus duty. Premiered on May 26, 1728, it was one of the many operas that Telemann composed for the Theater am Gänsemarkt – the Goose Market – in Hamburg. Unusually, the subject was drawn not from ancient history or myth but from recent events. In 1722 a sevenmonth siege of Isfahan led to the downfall of the Persian Safavid dynasty. The invader was an Afghan prince from Kandahar. His name was Mahmud, while one of the ousted shah’s sons was called Safi: it is they who appear in the fictional story of the opera. Safi is called Sophi – no problem there – but the librettist gave Mahmud the name of his real-life father, Mir Wais, who had died in 1715. Now concentrate, because this is where things get complicated. The opera’s Miriways (pronounced, roughly, MirryVice) is not married to his lover Samischa, because his father requires him to marry into the Mogul royal family. However, they have produced a daughter who, unaware of her parentage, has been brought up as the sister of Nisibis. Miriways wants his intended successor Sophi to marry his daughter; but Sophi refuses, as he is in love with Bemira. (Johann Samuel Müller, the librettist, quite fails to exploit the irony of the situation.) Of course, Bemira and Miriways’s daughter are one and the same. The other love interest is between the widowed Nisibis and the Tartar prince Murzah, brother of Samischa. Nisibis is also pursued by Zemir, a Persian prince, who behaves badly but is not really a villain. So, nobody dies. Müller’s stagecraft is pretty feeble. Bemira has been separated from her parents since infancy, yet there is no joyful reunion. After three occasions on which he claims the credit for what Murzah has done, the jealous Zemir avoids a duel by running away – no aria of defiance or remorse – never to be seen again. The action proceeds through the familiar sequence of secco recitative and aria (all but two are da capo); there’s one duet, and an accompanied recitative – all 27 seconds of it – for the ghost of Shah Abbas the First. The music is attractive but, on the whole, bland. Once in a while Telemann will do something unexpected, such as the fading away when Nisibis falls asleep, or the teasing hemiolas of Zemir’s ‘Die Dankbarkeit wird dich verpflichten’. The aria where Miriways rails at Sophi for his ingratitude starts dramatically with no introductory ritornello; later on there’s some fine contrapuntal writing for the strings. The orchestration includes flutes and oboes d’amore, which sometimes double the vocal line; a bouquet especially for Erwin Wieringa and Miroslav Rovensk≥ for their virtuoso horn-playing. The cast is uniformly excellent. The track list indicates that several numbers have been omitted, so it’s impossible to tell whether the original balance of arias has been maintained. Miriways has the most but the action is really centred on the two pairs of young lovers. André Morsch brings such authority to the part as the music allows. The other baritone, Michael Nagy, sings tenderly when observing Nisibis asleep, and is suitably virile when challenging Zemir. In the trouser role of Sophi, Robin Johannsen is also heroic, but finds a touching wistfulness in the aria that concludes the second act. Nisibis rejects Zemir’s attentions with roulades expertly dispatched by Lydia Teuscher. Bad boy Zemir, another soprano role, has some of the best music: Anett Fritsch delivers a spirited aria mocking his rival, and relishes the syncopations of ‘Die Dankbarkeit’. Sophie Karthäuser sings her two arias so appealingly that it’s a shame there’s no love duet for Bemira and Sophi. No complaints about Bernard Labadie and the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, nor about the live recording: the only applause comes at the end of each act and after the sole comic turn, Scandor’s drinking song. The libretto includes passages of recitative that are not actually sung. One of them, ‘I fell asleep in a seat, as I wanted to be frisky this morning’, gives you a good idea of the ineptitude of the translation. Another example is Samischa’s ‘My sororal heart elates’. And it is extraordinary that, for an opera set among the superb Islamic monuments of Isfahan, the sole illustration in the booklet should be of ancient Persepolis. |

|