Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

Reviewer:

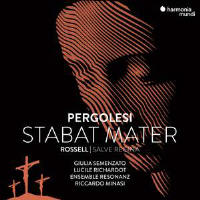

Tim Ashley We know little about the genesis of Pergolesi’s Stabat mater other than that it was composed in 1736, during his final illness, for the same Neapolitan confraternity that had commissioned Alessandro Scarlatti’s setting a decade beforehand, and that it was originally intended for two castratos. Pergolesi’s most popular work, it has proved remarkably malleable over time, admitting multiple approaches, ranging from oncefashionable choral adaptations to today’s stripped-back period-band austerity, via some truly remarkable pairings of great singers (Evelyn Lear with Christa Ludwig, Mirella Freni with Teresa Berganza: the list is extensive). The two most recent additions to its discography tackle it in very different ways. Riccardo Minasi and Ensemble Resonanz use conventional instruments tuned to mean-tone temperament, period bowing, and the standard pairing of soprano (Giulia Semenzato) and mezzo (Lucile Richardot). Marie Van Rhijn and the period Orchestre de l’Opéra Royal, meanwhile, aim to get as close as possible to the way the work might have sounded at its first performance, replicating the small forces of an 18th-century Italian church orchestra, with a male soprano, Samuel Mariño, alongside countertenor Filippo Mineccia. Interpretatively they are poles apart, with Van Rhijn opting for reflection and restraint, while Minasi offers something altogether more radical. At times almost shockingly intense, his performance is rooted in an exacting realisation of the implications of the text, with its emphasis on physical suffering and spiritual ardour. Harmonic clashes grieve, lacerate and rend. Trills and sforzandos suggest the sword thrust (‘pertransivit gladius’) that plunges the Virgin’s soul into torment, while the strings at ‘et flagellis subditum’ really scourge and sting. The fires of zeal burn terrifyingly bright in ‘Fac ut ardeat cor meum’, though the emotional climax comes at ‘Quando corpus morietur’, with the eventual resolution of dissonance and agony into spiritual calm. Minasi’s slow speed here results in time itself almost standing still, and when we reach the final ‘paradisi gloria’, we really do seem to be gazing suddenly into eternity. Semenzato and Richardot are tremendous. Richardot’s warmth offsets Semenzato’s brightness, and their voices blend and twine round each other almost sensually in their duets. Semenzato’s way with ‘dum emisit spiritum’, her tone draining away as the breath leaves Christ’s body, is astonishing. In ‘Fac, ut portem Christi mortem’, Richardot spins out fantastically decorated lines in contemplation of Christ’s wounds before closing the aria with a big cadenza on the final ‘ob amorem Filii’. ‘Quando corpus’ is ravishing, a sequence of immaculately sustained pianissimos that hover and drift ecstatically before both voices gradually come to rest in unison. It’s an outstanding achievement, which Van Rhijn’s never quite matches, fine though much of her recording is. The mood, enhanced by the lean orchestral tone, is one of devotional austerity, and just occasionally we could do with greater weight in the string sound. She pushes forwards urgently at times. ‘Quae moerebat’ feels fractionally too fast but Mineccia, whose singing can often be so extraordinarily beautiful, is effortful in his upper registers here, despite the liquidity with which much of the music flows. As with Minasi’s performance, the two voices blend and twine most sensuously. And Mariño is unquestionably remarkable, his tone silvery, appealing and easy, even in his upper registers. Both singers here, though, are perhaps shown off to better advantage in the accompanying Vivaldi motets. Though Mariño and Van Rhijn don’t quite equal the sheer panache and élan of Simone Kermes with the Venice Baroque Orchestra and Andrea Marcon (DG, 6/07), they do spectacular things with In furore iustissimae irae, where his coloratura flows superbly and his slow central da capo aria is exquisitely shaped. Vivaldi’s Stabat mater, meanwhile, keeps Mineccia away from his troublesome upper registers, and his singing has astonishing warmth of tone and restrained fervour. Even here, though, Van Rhijn’s disc has to yield pride of place to Minasi’s, where the coupling is the Salve regina a due, now known to have been written around 1742 by the Catalan composer Joan Rossell, though for centuries it was attributed to Pergolesi, partly, one suspects, because of melodic similarities, possibly plagiaristic, between the Stabat’s ‘Quae moerebat’ and Rossell’s own alto aria ‘Ad te clamamus’. A work of exceptional beauty, it forms an ideal companion piece to Minasi’s Pergolesi, effectively resolving its tensions and drama into a mood of ecstatic contemplation. Minasi conducts it with wonderful depth of feeling, and the way Semenzato and Richardot spin out Rossell’s long-breathed lines is close to perfection. It really is a breathtaking album. Do listen to it. |

|