Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

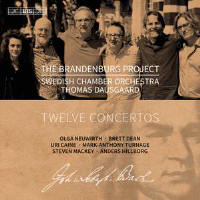

Reviewer: Andrew Mellor We take familiar works such as the Brandenburg Concertos for granted, argues Thomas Dausgaard in his booklet note. Other composers can reconnect us with the special qualities of these works, he says, from whose detailed delights we have been immunised by over-familiarity. The Swedish Chamber Orchestra’s ‘Brandenburg Project’ asked six composers to chose a concerto and write a response piece for the same forces (they were allowed to substitute one instrument). ‘Would it result in a meaningful whole?’ Dausgaard asks. You may have your own answer if you were present at the pair of 2018 BBC Proms during which all 12 works were performed. Mine, based on this recording, is no: ‘The Brandenburg Project’ doesn’t result in a meaningful whole, given the composers respond with varied ideas of what a complementary or reflective work can be, which makes for a collection uneven in form despite the backbone provided by Bach. But there’s no doubting Dausgaard has accomplished his mission to make us hear these pieces differently. His ‘Brandenburg Project’ is nourishing and frequently a lot more, but it undeniably asks another question: whether composers are more consistently at their best when setting their own restrictions of instrumentation, inspiration, duration and concept. The best of the new works are those that take Dausgaard’s commission most obviously at its word. After a Brandenburg Concerto No 4 with a particularly delectable Andante, Olga Neuwirth gives us Aello, a ‘ballet mécanomorphe’ in three movements that Dausgaard neatly summarises as ‘the wildest’ of the commissions but also ‘the closest to Bach’. Its score is an instinctive but umbilical reaction to Bach’s rhythmic ingenuity in which instrument groups are tuned to four different pitches. harpsichord is doubled by typewriter, while elsewhere a battery-powered milk frother and a synthesiser contribute to a deeplistening response to Bach, even when it’s sounding like ’90s Nintendo music. Uri Caine’s three-movement Hamsa is a similarly direct product of a delicately performed Concerto No 5 in which Mahan Esfahani is notably restrained in the big cadenza (he provides plenty of flair elsewhere). Like Neuwirth, Caine transplants the motoric Baroque pulse on to a bigger canvas coloured with a wider palette, the result more like neoclassical Stravinsky whose spiky, angular textures throw up fragments of JSB; an ironically grand piano cadenza (played by Caine) sees the first movement ‘Fast’ dissolve into shards and end with faux-classical formality. The work grows in complexity but in so doing strays beyond the bounds of Bach’s lucidity. Brett Dean’s Approach: Prelude to a Canon is the one new work intended to be played before the Brandenburg in question, in this case No 6. The composer sets out to establish ‘two contrasting temperaments between the soloists [in order] to find a point of reconciliation between them that leads us into [a] close contrapuntal companionship’, which extends from a tight reactive weave to what sounds like the two solo violas hocketing the same line. The Bach that it is segued straight into takes Dean’s approach of guiding listeners into the counterpoint rather than assaulting them with it – a distinctively introspective performance, calming but sophisticated and suggesting that this journey through Bach’s scores alone has taken the ensemble somewhere. Anders Hillborg responds to the concerto grosso’s roots in improvisation. His Bach Materia follows the lively bustle but sophisticated blend of the Swedish CO’s Concerto No 3 (its third movement seasoned with an outlandish harpsichord glissando from Esfahani), a performance that leans into corners with relish. Hillborg fills in the ‘missing’ middle movement relatively insubstantially (at least it’s improvised, as the manuscript suggests), which upsets the aesthetic and arguably undermines the neat opening to his piece proper, whose first movement plays with the harmonic cascades of Bach’s opening movement with a disco vibe that doesn’t let us forget Hillborg once wrote Swedish pop music. It’s done with a spirit of conversation and of the dance, aided and abetted by Pekka Kuusisto’s shamanistic violin (Kuusisto sings and whistles his way through the second movement with Sebastien Dubé’s slap bass for accompaniment). But Hillborg’s improvisatory roadmap isn’t immune from faceless noodling. The Swedish CO’s Concerto No 1 is full of keen phraseology, with polished horns but at a lick that gives the impression of some strings not keeping up. Some of the frolicking ornamentation can seem a little contrived without the impulsive larks of Esfahani at the harpsichord. Its companion piece is Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Maya, in which a cantor cellist (Maya Beiser) strings a single incantation over irregular rhythms. A distant horn traces the horizon during an uneasy wind interlude before the cello returns and leads a big cadenza. Perhaps the link there is a spiritual one – it’s hard to point to a technical one – and this is certainly one of two new concertos that reflect our more narcissistic age, music revolving more around individual than collective power. Another is Stephen Mackey’s Triceros, in which Håkan Hardenberger pick up three trumpets – following an extraordinary turn in Concerto No 2 in which he seems as light and fluent as a tweeting bird – to appear both lonesome and heroic. Without going as far as Hillborg’s explicit call for improvisation, the piece gives the impression of being an imitative jam, layering up patterns, tempos and reactions as it spools out over distinct sections. Its restless groove gravitates back to Bach and eventually docks into the Brandenburg’s own trumpet figurations. The skill of the composer, and the joy of the apotheosis, is in how clearly you hear it coming. |

|