Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction |

|

|

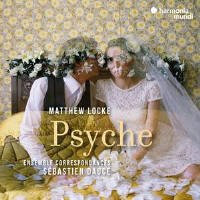

Commissioned by the actor-manager Thomas Betterton, Psyche opened at the Dorset Garden Theatre in London on February 27, 1675, in the presence of King Charles II and his court. It’s one of the earliest plays with music known as semi-operas, of which Purcell’s King Arthur and The Fairy Queen are the best-known examples. The book and lyrics by Thomas Shadwell – somehow ‘libretto’ doesn’t seem the mot juste – were based on Lully’s tragédie-ballet Psyché of 1671 (not to be confused with his later opera of the same name), which Betterton had almost certainly seen when visiting Paris.

The music was by Matthew Locke, one of the contributors to Shadwell’s earlier adaptation of The Tempest, with most of the purely instrumental numbers composed by Giovanni Battista Draghi, an Italian resident in London. The cast was made up of an enormous number of actors, singers and dancers; the production was spectacular, the scenery alone costing over eight hundred pounds. The complicated plot turns on the love between human Psyche and divine Cupid, neither of whom sing; while the characters include Psyche’s jealous sisters (who, in the current jargon, try to ‘gaslight’ her), unsuccessful suitors who are murdered, and any number of gods, devils and allegorical figures.

The published score of 1675 (under the heading of ‘The English Opera’) lacks detailed instrumentation, and Draghi’s contributions are omitted. As well as fleshing out the orchestral parts, therefore, Sébastien Daucé has both adapted some of Locke’s consort music and raided a manuscript collection called ‘The Rare Theatrical’. Without the extensive spoken dialogue this recording can’t, and doesn’t, make much sense as a drama. Better to enjoy it as an entertaining sequence of recitatives, songs, choruses, dances, ‘symphonies’ and ‘entries’, most of them short. The one extended piece is the ‘Italian Lament’ from Lully’s Psyché (included in both the ballet and the opera), which Daucé inserts at the end of the second of the five acts. Nothing here is as memorable as what you will find in Purcell but Locke’s influence on the younger man is clear. The drinking song ‘Ye bold Sons of Earth’ was surely a model for ‘Your hay, it is mow’d’ in King Arthur.

Daucé’s direction of Ensemble Correspondances is impeccable, the instrumental numbers going with a swing. The vocal contributions are less distinguished. The singers make an excellent chorus but in solos one is all too aware that some of them are struggling with a foreign language: syllables are swallowed, vowels distorted. I haven’t heard the New London Consort’s 1994 recording under Philip Pickett, in an edition by Pickett himself and Peter Holman, but to judge from Jonathan Freeman-Attwood’s rave review it would be worth tracking down (L’Oiseau-Lyre, 2/96). |

|