Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction |

|

|

You might recognise the names of three of the characters listed above from two operas: Lully’s Roland (1685) and Handel’s Orlando (1733), not to mention Haydn’s Orlando paladino (1782). Like them, L’Angelica (1723) is one of the numerous works based on Orlando furioso, the epic poem by Ariosto published in 1516. The African prince Medoro is loved by Angelica, the pagan princess of Cathay; she is also loved – and pursued – by Orlando (alias the paladin Roland, nephew of Charlemagne). The cast is completed by Tirsi and Licori, shepherd and shepherdess, and Titori, who is Licori’s father. Misunderstandings and deception abound; all ends well for the four lovers, but Orlando goes mad (‘furioso’).

However, L’Angelica is not an opera but a serenata: a concert piece performed in a palace in Naples to celebrate the birthday of Elisabeth Christine, wife of the Habsburg emperor Charles VI. The text was by the young Metastasio, who was to become the go-to librettist for composers of opera seria throughout the 18th century. Orlando and Medoro were sung by castratos; as was the part of Tirsi, marking the debut of the 15-year-old Carlo Broschi, better known as the superstar Farinelli.

The handsome designs are by the stage director, Gianluca Falaschi. The action takes place round a long table, from which hang floral swags and on which are cutlery and glass, as well as dishes with large domes, the latter serving as props. Later, the table decorations are replaced by an assembly of ornate wedding cakes. The costumes range from extravagantly baroque to modern white tie and tails. The music consists, as you would expect, of a chain of secco recitatives and arias; the first of the two parts ends with a duet for Angelina and Medoro. Porpora has some surprises in store. The da capo of Licori’s ‘Ombre amene’ is interrupted by Tirsi singing the same tune for a few bars before the recitative takes over. Orlando has a single accompagnato recitative, leading into a fast, violent aria of rage (while a transparent fish – a whale? – supported by two barechested men with sticks bafflingly crosses and recrosses the stage). And Medoro addresses the moon in an 11-minute aria, ‘Bella diva all’ombra amica’, accompanied only by continuo and a solo cello (ravishingly phrased with a nice sense of rubato by the unnamed player). The orchestra of strings, oboes and horns is supplemented in ‘Ombre amene’ by a pair of flutes, doubtless originally played by the oboists. Metastasio’s libretto has its fair share of his trademark metaphor or simile arias. The action ends abruptly with Orlando going mad, with no suggestion of his subsequent recovery and acceptance of the love between Angelica and Medoro. A strange way to celebrate a royal birthday, one might think. The booklet note mentions a Licenza, where the poet addresses the empress and a brief choral passage (not ‘page’, translator!) brings the serenata to an end. If the music is extant, its omission is rather a pity.

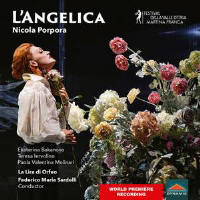

The predominantly young cast sing and act with verve. All the women are excellent, but I would single out Barbara Massaro for the sweetness of her soprano. La Lira di Orfeo under Federico Maria Sardelli play with spirit. Porpora, rival of Handel, mentor of Haydn, is worth exploring. Richard Lawrence |

|