Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

|

|

|

Reviewer: Michael

Carter It wasn’t that many years ago that the name of Jan Dismas Zelenka (1679–1745) was largely known only to musicologists. In the day, some of us were curious enough to have purchased a Decca vinyl disc with Zelenka’s Sinfonia a 8 and Overture in F Major performed by the New York-based orchestra of the Clarion Concert Society conducted by the late Newell Jenkins. In the intervening years, things have begun to change, even if slowly.

The value of Zelenka’s stock

has increased significantly in the last several years and to the point that

the name of this once-obscure Bohemian double-bass-player employed by the

court in Dresden is now being mentioned in the same breath as Bach and

Telemann (who both knew and respected Zelenka, and owned copies of his

work). Furthermore, the availability of recordings of Zelenka’s music has

increased to the point that in the case of some works (the trio sonatas and

orchestral works) we now have a choice of several recordings—using either

period or modern instruments—at our fingertips. Zelenka’s catalog of compositions looks quite small if placed beside those of Sebastian Bach and the seemingly inexhaustible Telemann, but in this relatively undersized collection lies evidence of an individualistic and extremely gifted composer. In an earlier interview published in Volume 25:4 of Fanfare, conductor Frieder Bernius observed, “I think it may take several more decades [for the public] to really appreciate this composer. His strengths are not to be found in the rich harmonic language or the balanced rhythm we know from Bach, but in imaginative formal development.”

Indeed, Zelenka’s music is

abundant in imagination, and more than occasionally his imagination is

idiosyncratic. These characteristics include, but are not limited to,

irregular phrase lengths, shifts between parallel major and minor tonalities

and—by the standards of his time—remarkable harmonic progressions (e.g., the

concluding measures of the opening movement to the Overture in F have the

ensemble finding its way home by way of the remote tonality of D♭ as opposed

to the expected dominant, or C). These “modernisms” aside, Zelenka was

astutely aware of and, to a degree, influenced by his musical ancestors; he

was a student of the great contrapuntist Fux, and his fugues exhibit a

strong sense of musico-rhetorical expression. Zelenka also effectively

employed cantus firmus and ostinato. So our composer was a man with one foot

in the past and another in his own time. It also should come as no surprise

that—given Zelenka’s tendency for the unorthodox—one at times hears things

that appear to adumbrate Classicism.

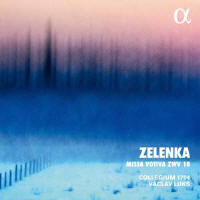

The masses recorded on these

CDs date from the 1730s, with Missa Purificationis being composed in 1733

and Missa Votiva dating from 1739; the Litany comes from 1744, the year

before Zelenka’s death. Sizeable forces are demanded for the Missa

Purificationis beate virginis Mariae. In addition to the normal complement

of strings, Zelenka’s opulent score employs oboes (who alternately play

flutes, as was expected at the time), bassoon, four trumpets, and timpani,

SSATB soloists, and SATB choir. The orchestra is reduced to four-part

strings with oboes and bassoon for the Missa Votiva. Here Zelenka retains

the SATB choir and also uses the standard solo quartet (SATB); identical

forces are pressed into service for the Litaniae lauretanae. The litany is

named after the shrine of Our Lady of Loreto (Italy), where the use of the

text appears to date from the middle decade of the 16th century.

The plan of the masses follows

the tradition of the so-called “number” mass: each segment of the text is

set as a separate movement, a plan that was common in the era. Missa

Purificationis beate virginis Mariae was not composed—as the title

suggests—for the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin on February

2, but on the occasion of the Queen’s first visit to the church following

the birth of her son. Missa Votiva was quilled—as its title indicates—to

fulfill a vow, apparently made during a serious illness. A note on the score

explains the title; it reads, Missa hanc A[d] M[ajorem] D[ei] G[loriam] ex

voto posuit J[an] D[ismas] Z[elenka] post recuperatam Deo Fautore Salutem. From the opening phrases of these compositions, there is no doubt that we are about to experience something special, even if it is in a Zelenkian sort of way. He places his seal on the genre with appropriate devotion and style, employing and deploying his forces with both agility and confidence. In the stylistic sense, the old is mixed with the new: choral passages that could have been written half a century earlier are placed alongside arias displaying the latest in operatic expression. Yet Zelenka is no mere copycat. When you least expect it, he toys with you, taking you in an unforeseen direction, melodically or harmonically, before again setting his feet on the expected path. For example, Zelenka expectedly establishes the home key at the opening of the Missa Purificationis and makes the ears comfortable. But then a rapid and unanticipated shift in harmony occurs before a curious and quasi-wandering unison passage takes us back to D Major. The “Qui tollis” opens with a fugal subject that sends the chorus through a sort of harmonic labyrinth before resolving into the radiant D Major opening of the “Qui sedes.”

The Missa Votiva is also

stunning in its invention, with numerous impressive moments, including a

rather oddly structured “Gratias agimus tibi,” not to mention some quirky

phrasing and unexpected chromatics in the “Quoniam.” Then there’s the “Crucifixus,”

whose fugue takes more than one unanticipated route toward resolution before

launching headlong into “Et resurrexit,” which holds its own set of

surprises.

Each of these recordings heaps

glory upon glory by way of their exceptional advocacy, that advocacy being

well placed, given Zelenka’s musical sphere. The tonal beauty and clarity

produced by the soloists and choirs is easily matched by the clean, but

never antiseptic playing of the period-instrument orchestras that contribute

to the mix with a nice luster and razor-sharp precision, resulting in

performances that exhibit compelling enthusiasm and unparalleled advocacy.

The sound is natural and sweet and is buoyed by the marvelous acoustics of

the venues. Given the number of recordings of Zelenka’s music in recent years, I cannot imagine the adventurous or discriminating collector either not being familiar with or not owning any recordings of his music. But there must be some among you and if you want to take a chance, don’t stick your toe in the water. Just jump in with either—or both—of these discs; you’ll be in for a real musical experience, and you’ll probably get hooked just as I did!

| |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|