|

|

|

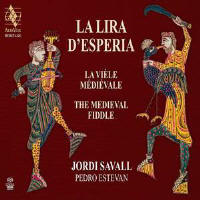

La Lyre d’Hesperia 1100-1400

Depuis la nuit des temps, il existe de constantes références aux pouvoirs et effets extraordinaires de la musique et des instruments qui la servent sur les personnes, les animaux et même les arbres et les plantes. Ceci constitue justement les attributs les plus caractéristiques d’Orphée qui grâce à ses talents et sa magie de musicien est devenu l’un des mythes les plus mystérieux et les plus symboliques de toute la Mythologie grecque. D’origine immémoriale, ce mythe en se développant est devenu une véritable théologie autour de laquelle existe une abondante littérature souvent de caractère ésotérique. Orphée est le Musicien par excellence, celui qui sait jouer des mélodies enchanteresses captivant les bêtes sauvages, qui fait s’incliner les arbres et les plantes et calme totalement les hommes les plus féroces. L’Hesperia (Esperia, en italien) était le nom que l’Antiquité donnait aux deux péninsules les plus occidentales : l’italique et l’ibérique. C’est également vers ces latitudes de l’extrême Occident – selon Diodor – que semblent se situer les Hespérides ou Atlantides, fameux jardins où se trouvaient les pommes d’or aux pouvoirs magiques (oranges ou citrons ?). C’est précisément dans l’Hesperia ibérique que nous trouvons les premières traces d’instruments à archet. Inconnue dans l’Antiquité et au tout début du Moyen Âge, la technique de l’archet semble, selon une très probable hypothèse, s’être développée peu à peu en Europe à partir des Pays arabo-islamiques. Souvenons-nous du haut niveau de la culture arabe et byzantine du Xe siècle et de l’importance des échanges artistiques souvent liés aux conflits eux-mêmes entre l’Orient et l’Occident. Il n’est pas étonnant que les premières représentations d’un instrument à archet apparaissent en Europe dès le Xe siècle dans les manuscrits mozarabes d’origine hispanique du Beatus de Liébana (920-930) ainsi que dans divers manuscrits catalans tels que la Bible de Sainte Marie de Ripoll. Ainsi apparaît la Vièle, l’instrument préféré des Troubadours[2] et des Jongleurs[3] mais aussi des Nobles qui, après leurs qualités guerrières, valorisent tout particulièrement leur habileté à jouer de la vièle. Il est permis de déduire cette affirmation à partir de nombreux textes de l’époque ou d’images aussi évidentes que les « sceaux » de Bertrand II, comte de Forcalquier (Provence) qui, en 1168, est représenté d’un côté à cheval avec ses armes et de l’autre en train de jouer de la vièle. C’est pourquoi on parle de noble joglere par opposition aux jongleurs professionnels, car leur activité n’est pas liée au profit mais au simple plaisir : ceci fait partie déjà des exercitia liberalia. La vièle est donc par excellence, et au même titre que la harpe, l’instrument indispensable à la vie courtisane et seigneuriale. Malgré toutes ces importantes informations iconographiques et littéraires, il nous faut constater l’absence pratiquement totale d’instruments à archet originaux antérieurs au XIIIe siècle. Le premier instrument à archet à 5 cordes (environ 1255-1275) a été trouvé en Pologne lors d’excavations réalisées en 1941. Pour une bonne compréhension des caractéristiques et du fonctionnement de ces instruments, il est utile de posséder un maximum d’informations : I – Iconographiques qui proviennent des différentes représentations d’instruments pendant toute la période médiévale, sur les chapiteaux et dans les cloîtres, sur les fresques, les peintures, les enluminures, les vitraux, etc. II – Historiques et Littéraires grâce à de nombreuses références à des instruments de musique, à la technique, à la construction et la fonction les concernant qu’on voit apparaître dans les chroniques et autres textes littéraires, philosophiques ou musicaux. III – Musicales par des œuvres originales existantes ou des œuvres qu’on peut reconstruire à partir de manuscrits de musique vocale de l’époque. IV – Traditionnelles à partir des nombreuses recherches sur le patrimoine musical populaire de transmission non écrite, conservé dans un état de pureté historique et formelle. Face à la tâche de recréation de ce répertoire médiéval, plusieurs problèmes de base se sont posés : Quels instruments ? Quel son ? Quelle musique ? En ce qui concerne les instruments, nous avons utilisé quatre types différents, tous avec des cordes en boyaux : 1. Une forme atypique de Rebab ancien, provenant d’Orient (Afghanistan) et datant probablement du XIVe siècle. Dans la Péninsule, on le connaît sous le nom de rabé morisco. Al-Farabi (environ 870-950) le considère comme l’instrument le plus proche de la voix humaine. 2. Une Vièle ou Rebec soprano à 5 cordes d’un auteur italien inconnu (probablement de la fin du XVe siècle). 3. Une Viole/Vièle ténor à 5 cordes, copie d’un instrument anonyme du XIVe siècle (Guy Derat, Paris 1980). 4. Une Lire ou Viole (soprano) à 6 cordes d’auteur italien inconnu (probablement du début du XVIe siècle). Si nous tenons compte des informations iconographiques, de la forme des instruments, du type d’archet et de cordes utilisées, il est évident que le concept d’idéal sonore de ces époques devait fortement différer de celui d’aujourd’hui. Seules les sonorités et les techniques de certains instruments populaires actuels tels qu’on les jouent en Grèce (Crète), Macédoine, Maroc, Inde etc., peuvent donner une idée approximative de ce qu’étaient les musiques de danse ou les musiques populaires : un son archaïque et parfois primitif mais plein de vie et d’expression et pour les musiques lyriques, poétiques ou musiques de cour : un son plus modulé et raffiné, comme nous le dit l’Archipreste de Hita en son Libro del Buen Amor, vers 1330 : La vièle à archet fait ses douces cadences, endormeuses parfois, parfois agaillardies : notes douces et agréables, claires et bien modulées ; des gens s’en réjouissent et le monde est satisfait. En ce qui concerne la musique, nous avons fait une sélection d’œuvres d’origines bien contrastées : · Œuvres écrites du Trecento italien et des Cantigas de Santa Maria d’Alfonso X le Sage. · Œuvres non écrites sélectionnées à partir de musiques populaires de tradition très ancienne, recueillies et étudiées par plusieurs chercheurs à la fin du XIXe siècle et début du XXe. Toutes ces musiques sont en relation profonde avec le monde si caractéristique de la culture de l’Hesperia ancienne, où vécurent ensemble durant tant de siècles les 3 cultures fondamentales du monde méditerranéen : la juive, l’islamique et la chrétienne. Dans cette optique, le programme comporte trois grandes sections et une conclusion. Chaque section contient un groupe de trois œuvres originaires de ces trois cultures et un groupe de 2 œuvres courtisanes provenant du manuscrit add. 29987 du British Museum (contenant de la musique italienne du Trecento). Comme l’indique Johannes de Grocheio[4] dans son Ars Musicae, les différentes formes musicales de cette époque ont des fonctions distinctes selon leur contenu et leur caractère : nous trouvons les cantus gestualis, cantus coronatus, cantus versualis, cantilena rotunda, et la musique instrumentale fait appel aux rotundellus, ductia et stantipes[5]. Toujours d’après lui, entre les divers instruments à cordes, celui qui ravit le plus est la vièle, au point que celle-ci in se virtualiter alia continet instrumenta (elle est capable de remplacer de nombreux instruments différents.) Bien sûr, ajoute-t-il, durant les fêtes et les tournois, les tambours et les trompettes encouragent les hommes, in viella tamen omnes formae musicales subtilius discernuntur. (Un bon vièliste doit pouvoir jouer tout chant et cantilène, et en général toute forme de musique.) Malgré qu’il s’appuie sur un maximum d’informations historiques et musicologiques, ce programme n’a pour objectif ni une hypothétique reconstruction historique d’un concert de l’époque ni le développement d’une recherche musicologique sur des faits dont nous ne connaîtrons jamais la teneur exacte avec certitude. Cette proposition est une tentative de recréation – inspirée par les styles correspondants à chacune de ces cultures – d’un certain art du son de l’archet à travers le temps et surtout une forme d’hommage à tous ces jongleurs et musiciens-poètes qui croyaient profondément qu’avec la musique « on pouvait pousser l’âme à l’audace et la force, la générosité et la gentillesse, toutes choses qui anoblissent la bonne organisation des peuples. » Ut eorum animos ad audaciam et fortitudinem magnanimitatem et liberalitatem commoveat, quae omnia faciunt ad bonum regimentum. JORDI SAVALL

|

|

|

ENGLISH VERSION The Lyra of Hesperia 1100-1400 The earliest string instruments described in Greek mythology, the lyra and the kithara[1] are among those most frequently cited by the Roman poet Virgil (70-19 B.C.). According to Greco-Latin tradition, Apollo invented the lyre, while Orpheus invented the kithara. From ancient times, there have been constant references to the extraordinary power and effects that music and musical instruments have over people, animals and even plants and trees. Such were the characteristic attributes of Orpheus, whose magical gifts as a musician inspired one of the most mysterious and symbolic myths in Greek mythology. With its origins lost in the mists of time, this myth gradually took on theological proportions, giving rise to a vast and often esoteric body of literature. Orpheus is the musician par excellence, whose enchanting melodies charmed wild beasts, caused trees and plants to bend down before him and soothed even the fiercest of men. Hesperia (Esperia in Italian) was the name given in Antiquity to the two most westerly peninsulas, the Italian and the Iberian. According to the Greek philosopher Diodorus, this was also the location of the Hesperides, or Atlantis, a wondrous garden where the magical Golden Apples (…oranges or lemons?) were to be found. And it is in Iberian Hesperia that we find the earliest references to bowed instruments. Unknown during Antiquity and in the early Middle Ages, the use of the bow to draw sound from string instruments, according to one of the most likely hypotheses, seems to have been introduced into Europe via Arabo-Islamic countries. We should not forget the high degree of sophistication achieved by Arab and Byzantine cultures by the tenth century and the importance of the cultural exchanges – often as a result of conflicts – that existed between East and West. It is not surprising, therefore, that the earliest European representations of bowed instruments are to be found in 10th century Mozarabic manuscripts of Hispanic origin: Beatus de Liebana (c. 920-930) and in various Catalonian manuscripts, including the Bible from the Benedictine abbey of Santa Maria in Ripoll. The medieval fiddle thus emerged as one of the favourite instruments of the troubadours[2], jongleurs[3] and, in particular, of the nobility who enjoyed playing the fiddle when their martial pursuits were over, as may be seen from the many references in the literature of the time and from iconographical sources, such as the seal of Bertrand Il, Count of Forcalquier (Provence), which on one side represents him armed and on horseback, and on the other playing the fiddle. These noble musicians were known as nobles jongleurs to distinguish them from the professional jongleurs, their musical activities being for pleasure rather than a means of earning a living; music for them was one of the exercitia liberalia (noble or liberal pursuits). In medieval times, therefore, the fiddle (along with the harp) was indispensable to courtly and lordly life. Notwithstanding all these important iconographical and literary references, hardly any original bowed string instruments dating from before the 13th century have come down to us. The earliest example of a five-stringed bowed instrument (dating from c.1255-1275) was found in excavations in Poland in 1941. In order to understand the characteristics of these instruments and how they functioned, we need as much information as possible from the following sources: I – Iconographical: throughout the medieval period, instruments are to be found represented in sculpture (capitals, cloisters etc.), frescoes, paintings, illuminated manuscripts, stained-glass windows, and so on. II – Historical and Literary: numerous references to musical instruments and techniques, instrument-making and how the instruments functioned are to be found in chronicles and other literary, philosophical or musical texts. III – Musical: information may be obtained from extant original works or from works that can be pieced together from the manuscripts of vocal music from that time. IV – Traditional: much can be learned from all the research that has been carried out into our oral folk heritage, which has been preserved in an historically and formally pure state. When it comes to reconstructing this medieval repertoire, we are faced with a number of basic problems: Which instruments were used? What sort of sound did they produce? What music was played? Regarding the instruments, we have used four distinct types, all of them with gut strings: 1. An atypical form of ancient Rebab, from the Orient (Afghanistan) and probably dating from the end of the 14th century). In Spain it was known as a Rabé morisco (Moorish rebec). The great Muslim philosopher Al-Farabí (c.870-950) considered it to be the instrument that was closest to the human voice. 2. A five-stringed soprano Vihuela or Rebec made by an unknown Italian instrument-maker (probably end of 15th century). 3. A five-stringed tenor Viol/Vielle, copy of an anonyme instrument 15th century (Guy Derat, Paris 1980) 4. A six-stringed soprano Lira or Viol by an unknown Italian instrument-maker (probably early 16th century). Judging from the shape of the instruments and the type of bow and strings used as reflected in the iconographical sources, it is obvious that the concept of ideal sound at that time must have been very different from that of today. Only the sound and technique of certain present-day folk instruments, as played in Greece (Crete), Macedonia, Morocco, India, and so on, can give us a rough idea of what this ancient music must have been like: in dance or folk music, the sound may be archaic and sometimes primitive, but the result is always full of life and expression; where lyrical, poetical or courtly music is concerned, the sound is more modulated and refined, as the Spanish poet and ecclesiastic Arcipreste de Hita tells us in his Libro de Buen Amor (c.1330): The fiddle with its sweet

melodies, Regarding the music, we have chosen works from a variety of sources: · written works from the Italian Trecento and the Cantigas de Santa María by Alfonso X the Wise. · unwritten works selected from folk music of very ancient tradition, collected and studied by various researchers in the late 19th and early 20th century. All these pieces are closely related to the cultural world that was typical of ancient Hesperia, where the three main cultures of the Mediterranean world – Jewish, Islamic and Christian –existed side by side for so many centuries. With this in mind, we have divided the programme into three sections plus a conclusion. Each section contains a set of three works from these three cultures, plus two pieces of courtly music taken from a manuscript in the British Museum (add. 29987) containing 14th century Italian music. As Johannes de Grocheio[4] points out in his Ars Musicae, the different forms of music at that time had distinct poetic and social functions, according to their content and character: among the songs in the vernacular, he mentions the cantus gestualis, the cantus coronatus and the cantus versualis, and for instrumental music, the rotundellus, ductia and stantipes[5]. He also describes the bowed fiddle (vihuela de mano) as the most delightful of all string instruments: in se virtualiter alia continet instrumenta (it is capable of replacing many different instruments). Of course, he adds, during feasts, tournaments and jousts, drums and trumpets are also used to fire men with passion, but in viella tamen omnes formae musicales subtilius discernuntur (in the fiddle all sorts of subtle music are to be discerned). Although based on the maximum historical and musicological evidence, this programme is not intended to be either a hypothetical historical reconstruction of a concert of that time or a musicological study of facts that cannot – and will never – be known with absolute certainty. What we propose here is an attempt – inspired by the styles corresponding to each of the cultures concerned – to recreate a certain art of sounding the bow over time. Above all, this programme is a tribute to all the jongleurs and poet-musicians who were convinced that through music the soul could be moved to boldness and valour, magnanimity and generosity – all qualities that dignify the good governance of peoples: Ut eorum animos ad audaciam et fortitudinem magnanimitatem et liberalitatem commoveat, quae omnia faciunt ad bonum regimentum.

JORDI SAVALL Translated by Jacqueline Minett

\l "NOTES: [1] The lyra originally had a sound box made from a tortoiseshell and was used for musical education and amateur enjoyment. The kithara was the instrument of professionals and was used in musical contests, public festivals etc.; its sound box was constructed from wood. [2] Members of a class of lyric poets, living in southern France, eastern Spain and northern Italy from 11th-13th c., who sang in Provençal (Langue d’oc) chiefly of chivalry and gallantry; sometimes including wandering minstrels and jongleurs. (O.E.D.) [3] Medieval itinerant minstrels, who sang, played an instrument and composed ballads, told stories and otherwise entertained people ‘ [4] French music theorist who was flourishing round about 1300. [5] Grocheio divided musica vulgaris (in the vernacular) into two categories, cantus and cantilena. Each of these was then given a triple subdivision. The three forms of the cantus were cantus gestualis, cantus coronatus and cantus versiculatus (or cantus versualis). Cantus gestualis obviously meant chanson de geste, but the distinction between the other two is not at all clear. The term cantilena was applied to the secular refrain forms that Grocheio identified with the music of the people of northern France – hence the three subdivisions: rotundellus (rondeau), and (without text) stantipes (estampie) and ductia. The ductia was a textless instrumental composition with a regular beat – e.g. the pieces entitled danse in the Manusctit du Roi. (For all these subjects, see articles by H. Vanderwerf and E.H. Sanders in the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.)

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|