Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

|

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

|

|

|

Reviewer: Barry

Brenesal

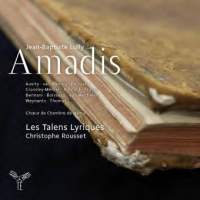

Traditionally, The Sun King had suggested subjects that promoted a view of himself as an Attic Greek god or hero; sometimes, both in the same opera. Amadis substituted a chivalric hero of Christian times: sensitive, gentle, and courteous, but a veritable demon in battle who always emerges victorious against whatever odds he faced. (He was, in fact, the model parodied by Cervantes in the character of Don Quixote.) Little else had to be changed from Lully’s previous tragédies en musique: For spectacles of the gods, nymphs, kings, and godlike heroes, Amadis substitutes magicians, fairies, knights, and princesses. Zeus may have no longer descended to solve everybody’s problems from within a cloud, but the fairy mage Urgande utilizes another speedy means of 17th century operatic transportation, a giant serpent. The work’s extravagant tale and cardboard villains don’t lend themselves to the kind of taut tragedy of Thésée (1675) and Atys (1676), but there are a few instances of Quinault’s shrewd insights into human nature. Musically, Lully continued his recent movement begun in Bellérophon (1677) towards récitatif obligé, with its freer textual patterns. The orchestra in turn plays a growing part in the proceedings—as in Arcalaüs’s “Dans un piège,” where typically for this opera more the half the air is performed before the vocalist enters, utilizing the same thematic material. The cast features several of the regulars Rousset has come to depend upon in the recent past. Sweet-voiced Cyril Auvity takes on the eponymous role with characteristic agility and sensitivity to color. His “est-ce vous, Oriane?” is one of the highlights of the set. Ingrid Perruche is a dramatically expressive Arcabonne; and Judity van Wanroij, best characterized as a dark mezzo with a soprano extension (though she’s listed as a soprano), a regal Urgande who tosses off figurations with disdainful ease. Among the others who I haven’t heard in Rousset’s previous productions, Edwin Crossley-Mercer impresses most with the strength and darkness of his bass-baritone. Rousset is for the most part as fine as ever, providing energy, discipline, and strong support to his singers. I was a bit taken back by the fast pace and stiff phrasing of “Bois épais,” arguably the most famous number from the work, and one of the best-known from Lully’s operas; but presumably he was reacting to very slow, indulgent performances of the air that have appeared repeatedly on recordings in the past. There’s no stiffness to his reading aside from that, and he allows some of Lully’s most sensuous melodies (such as “Non, non, pour être invincible,” and “Fermez-vous pour jamais”) to unfold at their own slowly ripening pace. Despite being recorded on stage across three live performances, Amadis is well engineered. There are no instances of poor balance between singers and orchestra, or loss of tonal warmth from microphone distance. This is one of the strongest entries yet in Christophe Rousset’s operatic series on CD, and fortunately in one of Lully’s finer operas. The only drawback is the short timings, with one side coming in at under 42 minutes, another at slightly over 56. But performances such as these more than make up for it. Recommended. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|