Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: David Vickers

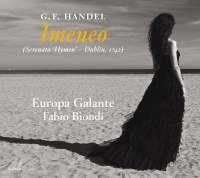

The libretto of Handel’s penultimate opera Imeneo is based loosely on the legend of Hymen, the Greek god of marriage: the Athenian maiden Rosmene has to choose between marrying for love (Tirinto) or for duty to the nation (Imeneo, who rescued her and other Spartan girls from pirates – admittedly because he was dressed up as one of the girls in order to stalk Rosmene).

Handel took two years to finish Imeneo and by the time it was eventually produced at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on November 22, 1740, many of its scenes had been substantially rewritten several times over. Instead, Fabio Biondi presents the drastically altered version performed twice at the culmination of Handel’s Dublin subscription concert series in March 1742 – the last occasions on which the composer directed an Italian operatic work. Biondi’s unreliable booklet-note unwisely disparages the 1740 London original in order to exaggerate the significance of the Dublin revision.

In fact, the essential role of Clomiri was obliterated and in numerous ways the plot was rendered with more holes than a colander. Tirinto’s enraged ‘Sorge nell’alma mia’ (written for a castrato) did not suit the technically limited alto voice of Susannah Cibber, so it was transferred expediently to Imeneo (now a low tenor rather than bass) to sing in a slightly later position; Magnus Staveland makes an brawny fist of it, and Europa Galante support with effervescent energy. Happily, the marvellous Ann Hallenberg retains Tirinto’s other outstanding aria, ‘Se potessero i sospir miei’ (based on David’s ‘O Lord, whose mercies numberless’), and gains a lovely aria lifted from Deidamia (‘Un guardo solo’). Monica Piccinini’s limpid singing aptly captures the superb accompanied recitative in which Rosmene feigns madness at the moment she is forced to choose between the two suitors. Handel’s interpolation of ‘Per le porte del tormento’ from Sosarme, a gorgeous love duet about reaching new bliss after having passed through torments, was given implausibly to Rosmene and Tirinto in the final scene of the Dublin serenata, where it makes no dramatic sense whatsoever (Rosmene has just settled in favour of Imeneo, not Tirinto). Perhaps dramatic coherence does not matter when such sublime music is sung and played so rapturously.

Europa Galante perform the Overture’s playful Allegro expertly, although Biondi’s anachronistic reduction to solo strings in the Minuet (led by florid solo violin) says more about his directorial priorities than Handel’s own practices; there’s some sly pizzicato invented for strings where Handel indicated none (eg towards the end of Rosmene’s ‘Semplicetta’), but his elegant obbligato playing in Rosmene’s ‘Ingrata mai non fui’ is irresistible. Fabrizio Beggi has a little bit of fun with Argenio’s simile aria ‘Su l’arena di barbara scena’, which mentions a savage lion who pauses from pouncing when recognising its victim had once pulled a thorn from its paw (Handel uses unison violas and violins, without harpsichord, to humorous effect).

Biondi’s accomplished performance,

recorded at the Halle festival last June, permits a valuable insight into

Handel’s pragmatism and reconstructs a historic event. Next we might hope for a

comparatively excellent advocacy of the 1740 original version to supplant

Andreas Spering’s abrasive and soulless 2003 account (CPO, 5/04). Mind you, both

Spering and Biondi boast Hallenberg on top form as differing incarnations of

Tirinto, so our glass is hardly half-empty. |

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|