Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Bill

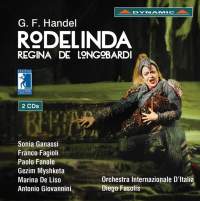

White During the Handel revival of the mid-to-late 20th century, record labels scrambled to record the German composer’s stage works, first the better-known titles, then the more obscure, on audio LPs and later CDs. A whole cottage industry of performers and musicians grew up around Baroque opera, particularly those of Handel. The impetus for this was only fueled further by the advent of early music instruments and performance practices, which then required a whole new round of recordings. Almost exclusively, these recordings were made in the studio, without audiences, and, some would say, often without the frisson and dramatic coalescence of a live performance. The operas were also often recorded more or less complete. But, in the last 25 years or so, the situation has reversed itself. Studio-born audio recordings of operas, Handel’s included, have slowly dried up due to increased recording costs and decreased sales. Today the operatic focus is on video recordings (DVD and Blu-ray) of live performances from the opera house. There the costs of soloists, chorus, and orchestra can be greatly mitigated by contractual arrangements with the unions and the singers themselves. Live performances also mean one must live with performance cuts, particularly in long Baroque operas as Handel produced. The desire to get folks home at a reasonable hour and not bore the pants off them is quite understandable. Upon a cursory look at this new audio CD recording of Handel’s Rodelinda on the Dynamic label, folks may think they are back in the good old days when new Handel opera recordings were flying around fast and furious, but such is not the case. Recorded in 2010, this is actually a live recording of a performance (or performances) from the opera house in Martina Franca, complete with stage noise, audience applause (pretty quiet otherwise), and more importantly, substantial performing cuts. To cut a Baroque opera substantially one must either eliminate musical numbers entirely or make what are called internal cuts, the method used here. Most early Baroque operas employ so called da capo (from the head) arias in A-B-A format, where the singer reprises the A section after an intermediary B section. Internal cuts as performed here are to eliminate the A section reprise from several of the arias, making them about a third shorter. It is done judiciously here, but is a bit unfortunate, since the A section reprise is most often where the singers strut their wares, fire off the coloratura, embellish the vocal line, and use the tricks of the trade to impress and entertain. In Baroque days it was a specialty of the castratos. In truth, several arias do not require or are inappropriate for such treatment, and here those are mainly the ones that feel the axe. This recording brings with it some fine singing from a not so well-known cast headed by Italian mezzo-soprano Sonia Ganassi. Ganassi brings little Baroque experience with her to this small regional theater; her forte is bel canto. What she does bring is name recognition and star power, which I suspect the opera company needed more urgently. The Rodelinda role provides much of the heavy lifting in this opera, with seven arias and one duetto to be sung. Ganassi sings it all well, after eliminating a bit of early fog from her voice. She has a vocal range that lies somewhere around the borders between mezzo and true soprano. But Rodelinda is a high soprano role and it sounds like Ganassi had at least some of her music stepped down. This has the rather unfortunate effect on audio disc of bringing four of the vocal roles into the same general voice range, often hard to keep sorted out. On this recording, two of those roles are sung by countertenors, and easily distinguishable. Singing the part of Rodelinda’s presumed dead husband, Bertrado, countertenor Franco Fagioli performs magnificently. Handel originally wrote Bertrado for the bravura castrato Senesimo, with fewer arias than the lead but most of the florid music, including the two best known arias, “Dove sei” from act I and “Vivi tiranno” from act III. Fagioli sings it all with great technical control and artistry, quite possibly the best on disc. The other four roles are sung by a contralto, alto countertenor, tenor, and bass. All are sung well here by this cast, although Handel does not really challenge these particular voices. Rodelinda is a rescue opera, rather the inverse of Beethoven’s Fidelio, where the wife in disguise rescues the husband from prison. Here, Rodelinda is the captive, her husband, the deposed king, presumed dead. But, of course, he isn’t, and in disguise goes about rescuing Rodelinda from the evil usurper. For many years now, the recording on Archiv led by Alan Curtis has been considered by many the bell weather set. One of those studio recordings mentioned earlier, it is nearly complete. The singing on this new Dynamic recording actually matches up quite well to the Curtis recording; the Bertrado is much better sung here, and I prefer the Martina Franca Orchestra Interzionale d’Italia over Curtis’s own Il Complesso Barocco. There’s much to like on this recording, then, but the extraneous noises from the live performance and particularly the cuts in the music must leave the Curtis set as still the top choice. This one, however, can be highly recommended. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|