Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Joshua

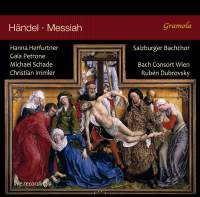

Cohen Another year, another Messiah (at least). In fact, this set was probably slated for last year: it was recorded live at an Easter concert at the Basilica Stift Klosternburg in March 2016, and its copyright is 2016. Never mind: The question is whether this version has anything important to say beyond what has already been said in the nearly 100 listed as available in the current ArkivMusic catalog. The short answer is “No.” This is a spruce, nicely played and (mostly) well-sung account of what the album cover identifies as the original Dublin version premiered in 1742, but which is in fact a slightly abridged version of the usual conflated edition. A few key numbers—for example, the alto-tenor duet “O death, where is thy sting” and the soprano aria “If God be for us”—are omitted entirely; “But who may abide” is given in the extended aria form written for the castrato Gaetano Guadagni in 1750, rather than the peremptory bass recitative used in all previous performances of the oratorio. Conductor Ruben Dubrovsky is a flashy conductor who knows how to show his players to best advantage. I couldn’t discern any long-range vision of the oratorio, but nothing drags or rushes off the rails. The dramatic episodes (“Thus saith the Lord,” “But who may abide,” “Why do the nations,” “Thou shalt break them”) are excitingly paced; passages of tragic contemplation or spiritual reflection tend to glide past a little too easily, even when they are beautifully sung. One eccentricity about the conducting (or possibly the engineering) is that the basso continuo is given unusual prominence, so that it tends to boom forth as an equal counter-voice to the higher strings and winds, rather than providing the harmonic underpinning of the music. It’s certainly interesting to hear the harmonic progressions register so assertively (and the splendid bassoonist deserves to be listed among the featured soloists), but the final effect is more distracting than enriching. Three of the four soloists are good, if not on the highest level. Soprano Hanna Herfurtner has a clear, flexible voice and a shapely way with the long phrases. She sails through the coloratura in “Rejoice greatly” and gives a touching account of “I know that my redeemer liveth” (with a more sensitive conductor she might have been even more eloquent). Christian Immler’s gritty but focused baritone rings out nicely in “The trumpet shall sound.” It is not the chocolaty-smooth sound I like to hear in Messiah basses, but it’s virile and incisive. Both singers pronounce the words clearly and almost without accent. Diction is more of a liability with the Italian mezzo-soprano Gaia Patrone, but she has good musical instincts (apart from a few awkward ornaments) and a darkly lustrous voice we should be hearing more of. Sad to report, it is the most distinguished soloist who lets the side down. German-Canadian tenor Michael Schade has been an important singer since the early 1990s. At his best he was an extroverted but cultured interpreter of the Mozart roles and Lieder, with a sturdy voice that could be surprisingly mellifluous in sustained cantilena. Unfortunately his tone has dried out over the years, while the artistry has become highly self-conscious, with an overabundance of fussy ornamentation and some strange sounding vowel distortions (“The rough places plane”). To refresh my memory of what he was like in his prime, I replayed his version of “Every valley” from the Harnoncourt set recorded in 2004. He was fairly flamboyant back then, too, but the voice was fresher and fuller, the vowels cleaner, and the overall presentation more spontaneous. It remains to report that the chorus (a mixed choir of 25 voices) and the orchestra are first-rate. The recorded sound is exemplary with respect to definition and dynamic range.

To

conclude, we have a pleasant but unremarkable concert traversal of Messiah,

of interest mainly to listeners seeking acquaintance with some promising

young soloists. With so many versions available I can’t offer a clear

recommendation. Among period instrument recordings I’ve lived happily with

the Hogwood set (though it’s clearly a relic of early days in the historical

performance movement); I also like what I’ve heard of Pinnock, Gardner, and

Cleobury (on DVD). A few months back, I enthusiastically recommended Jeffrey

Thomas’s DVD filmed in Grace Cathedral, San Francisco. Among “traditional”

versions with modern orchestras, Colin Davis and Mackerras (both from the

late 1960s) sound as eloquent as ever. And for those not averse to some

outrageous reorchestration, Beecham’s legendary/notorious 1959 recording

(with the Royal Philharmonic and the spectacular Jon Vickers singing the

tenor solos) remains a unique and thrilling experience. | |

|

Support us financially by purchasing this disc from eiher one of these suppliers. Un achat via l'un ou l'autre des fournisseurs proposés contribue à défrayer les coûts d'exploitation de ce site. |

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|