Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Bertil

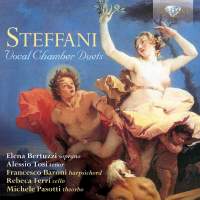

van Boer Few people during the Baroque period (or before or after for that matter) had the spectacular multifaceted career of Agostino Steffani. Born in 1654 and living to the ripe old age of 74, he encompassed the development of Italian music during that time, but also served in more non-musical capacities than one can imagine. A singer when young, he turned out to be one of the most prolific composers of opera, but in Germany not Italy. Indeed, during the first period of his career, not only did he function as an organist and develop the Bavarian court theatrical establishment, he was also appointed in a diplomatic role. After a short stint as a monastic abbot, he moved to Hannover and then on to the Palatinate, where he became the Rector at the University of Heidelberg, even then one of the most prestigious universities in the German realms. For a while, he was also apostolic ambassador to the Duke of Lorraine in Brussels, as well. By 1709, as an appointed bishop (of Spiga in Turkey, a place he never visited), he became the Pope’s representative in mostly Protestant realms, where he achieved a sterling reputation for his diplomatic skills, husbanding the welfare of the region’s Catholics. When his sovereign, the Duke of Hannover, became George I of England in 1714, his fame spread abroad, and he interacted with Handel and was appointed as honorary president of the Academy of Ancient Music a decade later. By his death in 1728 he was still at work in a diplomatic role. His musical activities apparently continued unabated from his youth until his final years, even though his career in music had long been superseded. Indeed, his cantatas and duets, of which seven are recorded here, were known throughout Europe for their beauty and inventiveness. Padre Martini considered them the epitome of graceful music, while Georg Philipp Telemann modeled his first operas on those of Steffani. Because of the smoothness of his writing, he is often seen as the anti-Scarlatti, preferring a more subtle style than the more stereotyped recitatives and arias of Alessandro Scarlatti, but in today’s view this may in reality reflect Steffani’s unique method that incorporates Italian lyricism with a more integrated Germanic structure as found in his contemporaries up north. The fusion results in some unique-sounding works. The duets are certainly some of the best known of Steffani’s smaller works. Composed for soprano, tenor, and continuo, they are delicately weaving arabesques of sound, in which both voices move about each other in complementary fashion. In “Gelosia, che vuoi da me,” for example, each asks the question of what jealousy is doing to them in imitative fashion that both allows for canonic entrances and overlapping lines. The sections are divided by short bits of recitative, as if the two singers were each in a corner commenting, each of which is followed by a brief arioso. At the end, both unite in floating parallel thirds, unifying what the jealousy had torn asunder. Unlike Scarlatti’s cantatas, these duets are interactive, with the drama more subdued. This does not mean that Steffani eschews virtuosity, for there are sections, such as the central portion of “Vorrei dire,” in which the lines tumble right along with flowing melismas. These are well integrated into the fabric of the work, rather than being showpieces, as one might expect of his younger Italian contemporaries, including Handel.

Soprano

Elena Bertuzzi has a clear voice, and her careful handling of the vibrato

(almost none) requires an absolute sense of pitch, particularly when she

duels playfully with tenor Alessio Tosi. Each complements the other well

(though Tosi does use a shade more vibrato), and the blend is quite nice.

They know instinctively how to reflect each other, and that helps the equal

lines of the music. The continuo is well placed in the background, and all

three performers provide a solid and subtle foundation, which is just what I

believe Steffani intended. In short, the disc is quite well done and

contains interesting music that really does show how varied Italian Baroque

could be, especially in the period around 1700. Given that he wrote well

over 200 of these duets, this is a good start, hopefully to both Bertuzzi

and Tosi doing more. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|