Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Barry

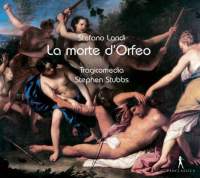

Brenesal This is a reissue of Accent 8746/47, originally reviewed by David Johnson in 1988 (Fanfare 12:2). L’morte d’Orfeo was written by Landi while in the service of Cardinal Scipione Borghese. (Grove I lists Landi as serving at the time Marco Cornaro, Bishop of Padua, but that can’t be right. Cornaro took part in papal conclaves that elected Popes Leo X, Adrian VI, and Clement VII—the last, in 1523, nearly a century before L’morte d’Orfeo.) The work was dedicated in June of 1619, and if it was performed, was done so privately. The only surviving copy derives from the Borghese library holdings. This puts Landi’s opera literally a dozen years after the premiere in the 1607 carnival season of Mantua of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, and another seven on top of that after the oldest known surviving opera, Jacopo Peri’s Euridice of 1600. On a literary level, it is a very different work from its predecessors. Where they remain reasonably close to the general outline of the original myth tale, Landi starts in media res: Euridice is dead, and various gods congratulate Orfeo on his birthday, while he mourns his lost beloved. Bacchus, angry over Orfeo’s snub to drink, love, and life, has his followers, the Maenads, attack and kill the poet. As a shade, Charon refuses him passage for lack of burial, but Mercury invites Orfeo to join the gods. Orfeo wishes to see Euridice instead; but when she appears she doesn’t remember him, having drunk of the River Lethe, which removes all memories of life. With the shock of this, Orfeo finally lets go of his love, and ascends to kneel before the throne of Jupiter. The work marks a further stage of development in early opera, in terms of the deployment of internal forms. Large-scale recitative still plays an important part—that of Calliope, in the fourth act, is a particularly fine example—but whole scenes, such as that of the Maenads, are now built around a succession of folk-like themes above consistent dance rhythms, while Charon’s lengthy drinking song, “Bevi, bevi, sicura l’onda,” looks ahead in some respects to Cavalli. So does the inclusion of a large cast, the increasing complexity of the opera’s act finales, and a declining use of massed polyphony in favor of monophonic song with simple accompaniment. I would second Johnson in his praise both for the style and technique of Stubbs’s Tragicomedia, and the various singers he engaged. John Elwes is an eloquent Orfeo, and Harry van der Kamp’s Charon makes a great deal of his song without lapsing into exaggeration. Wilfrid Jochens’s distinctive, higher tenor provides excellent contrast with Elwes. There isn’t a weak link in the set, if you discount the fact that the Italian text is presented in full, with only a short synopsis in English. The sound is a bit over-reverberant, but not enough to damage the contours of the music. All in all, this is a most welcome rerelease of a fine opera. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|