Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

International Record Review - (12/2013)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

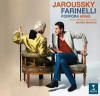

Erato

9341332

5099993413329 (ID328)

The trouble with singers such as James Bowman, Andreas Scholl and Philippe Jaroussky is that they sing (or sang) opera seria so well that they encourage hosts of lesser countertenors to do likewise. Currently, it seems the recording studios are crowded with male altos belting out arias by Handel, Vivaldi, Bononcini, Vinci, Hasse and Porpora. Many have an impressive vocal range and even some stylistic awareness in respect of da capo ornamentation and the like. What they usually lack, however, is a voice that is fundamentally beautiful and under complete control in matters such as pitch and vibrato. Yes, many of the arias they sing were originally written for male singers; but these were castrati, not countertenors, and there is nothing particularly authentic about having any old countertenor perform them simply because he is male. I strongly suspect a voice such as that of Simone Kermes is closer to what made opera seria audiences swoon when listening to singers such as Farinelli than the sounds made by most modem countertenors.

Of course, as noted, Jaroussky is a magnificent exception. His latest release (and his first on Erato, I believe) shows how the great castrato arias can and should be sung. The focus of this exceptionally lavish production is on Farinelli, the most famous castrato of them all, specifically arias written for him by the great Neapolitan opera composer and singing teacher Nicola Porpora (1686-1768), who was known to his contemporaries as ‘the high priest of melody’. The complex relationship between the composer and his star pupil and their friend and collaborator, the librettist Metastasio, is sketched in a brief essay by Jaroussky himself and exhaustively documented in a major essay by Frédéric Delaméa. The story has a poignant end, with Metastasio writing a begging letter to the fabulously successful Farinelli on behalf of Porpora, who was living in abject poverty. This disc, however, records happier times when the composer was creating roles and tailor-made arias for his star pupil’s appearances in Europe and in London. It was generally accepted that Farinelli was not much of an actor; but his facility in conquering the extraordinary demands of Neapolitan opera was astonishing. The librettist Paolo Rolli stated that before he had heard Farinelli he had ‘only been aware of a small part of what the human voice can achieve’. The singer’s exceptional breath control and vocal agility — both honed by Porpora’s exacting regimen allowed him to perform arias of staggering difficulty. According to Quantz, he possessed a ‘penetrating, full, rich, brilliant and well modulated soprano voice’. Increasingly as his career went from triumph to triumph, Farinelli added heart-stopping lyricism to his stylistic repertory: he was able to bring audiences to tears, not just to astound them.

As Jaroussky writes in his essay, no one knew Farinelli’s voice better than Porpora and the 11 arias and duets he has selected (seven of them reputedly premiere recordings) show every facet of the great singer’s talents. They allow Farinelli — and Jaroussky — to both dazzle us with wide vocal leaps and cascading trills (‘Mira in cielo’ and many others) and move us deeply with music of penetrating stillness (‘Alto Giove’, ‘Le limpid’onde’). Jaroussky’s technique in singing such demanding music is astounding throughout this recital; but the vocal pyrotechnics are only half the story. He also has an extraordinary gift for shaping a phrase with subtle perfection and for adding ornamentation that seems both spontaneous and utterly right. His favourite concert encore, the rapturous ‘Alto Giove’, is performed here in its entirety and rather better than the truncated and slightly disappointing version he recorded on his recent two-disc sampler set on Virgin. Unlike nearly all his countertenor rivals, Jaroussky almost never sounds shrill or gusty and rarely over-uses vibrato. He also shows great mastery of the messa di voce, for which Farinelli was also celebrated. It is a minor irritant that his partner in the two duets, Cecilia Bartoli, has few of these virtues. I know, however, she has her admirers (largely, I suspect, among people who do not otherwise listen to much Baroque music), so many will not be as unhappy as I with her (fairly brief) appearance.

An added delight is Porpora’s orchestral writing, which is exceptionally rich and well composed, going well beyond mere accompaniment to the point of equal partnership with the voice. Andrea Marcon’s Venice Baroque Orchestra is on great form, with a lovely burnished string tone, razor sharp precision in ensemble (including in the abundant trills), limpid period woodwinds and, in ‘Nell’attendere il mio bene’, thrillingly rasping horns and trumpets.

Obviously, we can never really know what Farinelli

sounded like; but this outstanding production by Jaroussky brings us

probably as close as we will ever get to this most celebrated singer of the

eighteenth century. Highly recommended.

Fermer la fenêtre/Close window

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews