Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer:

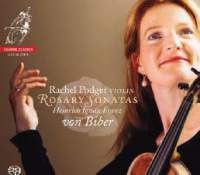

Michael De Sapio Among life’s certainties are death, taxes, and the fact that each month will turn up a half dozen new recordings of Biber’s Rosary Sonatas. It’s hardly surprising that this spectacular cycle should have become a favorite of Baroque violinists—though one wishes they would begin to show a comparable interest in the eight Sonatae violino solo of 1681, an equally magnificent set that unfortunately lacks the selling point of a programmatic storyline. In any event, it’s also unsurprising that Rachel Podger, one of the world’s leading Baroque fiddlers, should eventually come around to recording the Rosaries. I’ve had mixed feelings about Podger’s playing (having heard her only on recordings). I admire her secure technique, joyful spontaneity, and sinuous line; but she can also come across as too airy-fairy and lacking in gravitas, particularly in the more monumental works of the Baroque repertoire. Podger plays here with a predominantly small tone and rather restricted dynamic range. But the main thing missing from this Rosary Sonatas is a strong sense of expressive purpose. We hear beautiful music, but what is the music trying to say? Podger only intermittently provides an answer to this question. The “Annunciation” starts promisingly with some spontaneous and airy passage-work, and the “Visitation” is intimate and joyful. The “Nativity” brings a gently swinging, French-inspired Courente—for once we can believe that Biber intended to depict the shepherds in the fields—but the concluding meditation (in which Biber foreshadows the music of the “Crucifixion”) seems stuck in the mud. The “Presentation in the Temple” consists entirely of an eight-minute Ciacona of predominantly solemn tread; Podger fails to sustain sufficient expressive tension to maintain our interest in it, and the piece simply drags on. In the “Finding in the Temple” her buoyant bowing suggests an insouciant skipping home of the Christ child rather than the “eureka” moment of his finding; this is certainly a valid interpretation, but Podger dances on the border of flippancy. Moving into the Sorrowful Mysteries, the “Agony in the Garden” is tepid and listless, and Podger skips daintily through much of the “Scourging” (with its beautiful opening Allemande so suggestive of Christ’s meekness and innocence before his tormenters) and the “Crowning with Thorns.” In the “Carrying of the Cross” and the “Crucifixion” she belatedly discovers the tragic muse and, digging into her 1739 Pesarinus violin, produces a measure of dark intensity. Much of the passagework, however, remains lightweight. Christ is risen! But where is the sense of exultation? In the “Resurrection,” Podger’s staggered downward-rushing scales express nothing in particular, and her Easter-hymn-in-octaves sounds cautious. The fanfare-like repeated notes in the “Ascension” are choppy and prissified (the staccato marks in Biber’s manuscript might simply have been meant as an instruction not to slur). The abuse of short notes is a persistent mannerism here; there is no doubt that Podger understands the difference between “strong” and “weak” notes in a phrase, but the weak notes surely don’t need to be pecked and sniffed at. The continuo group goes all out on the rushing of the wind accompanying the “Descent of the Holy Spirit,” while Podger’s violin grows increasingly relentless and harsh, not to good effect. In the “Assumption of the Blessed Virgin” Podger and company treat us to an ebullient Ciacona with a thumping romp of a Gigue; this is “Biber as folk-fiddler,” and it really swings. The “Coronation of the Blessed Virgin” rounds out the Mysteries with a feeling of hard-won serenity. The concluding unaccompanied “Guardian Angel” Passacaglia is, in some ways, the most successful thing on the disc; this track was actually taken directly from Podger’s earlier Channel recording The Guardian Angel. Podger treats the piece as an array of improvisational episodes, and the result is a convincing alternative to a “steadily building progression” approach. At the 5:30 mark we encounter an unfortunate editing snafu: The wrong phrase was spliced in, with the result that what we hear sounds correct but isn’t what Biber wrote. Six different continuo instruments are heard in various combinations throughout the recording: organ, harpsichord, theorbo, archlute, cello, and viola da gamba. This creates a kaleidoscopically shifting soundscape (but how does Marcin Świątkiewicz jump from organ to harpsichord within the same sonata?). Most enjoyable are the sections in which Podger is accompanied by the harpsichord alone, since Świątkiewicz’s figurations are always pleasing; least successful are those in which she is accompanied only by the theorbo or archlute, as these turn rhythmically gelatinous. One longs occasionally for an occasional plain, unharmonized bass line to clarify the structure and get us settled in. This group has a habit of harmonizing immediately, even at the beginning of the ground-bass numbers (the Ciacona of the “Annunciation” is a case in point). The recorded sound is bright and clear, with Podger recorded at a comfortable range. The individual scordatura tunings (which Podger evocatively describes in her notes as causing the violin to “suffer”) come across in a most tactile manner. In the “Nativity” Sonata, for instance, the odd and unresonant tuning makes Podger’s violin sound almost ill; the effect is “contained and inward” with a “true sense of foreboding,” in Podger’s words. Each sonata is assigned a single track—a very good idea. Both the individual scordatura tunings and the continuo combinations for each sonata are helpfully listed in a table on the back of the booklet. My go-to version of these works is the classic 1989 recording with John Holloway and Tragicomedia. Holloway combines a splendid mastery of Biber’s virtuosic flourishes with golden tone, noble simplicity of utterance, and a dramatic urgency that is largely missing from Podger’s version. He and his varied continuo players make memorable theatrical scenes of episodes such as the “Crowning of Thorns,” where the Guigue with its blatant laughing motif becomes the occasion for using the regal (a nasally chamber organ) to suggest the mockery of the soldiers. Andrew Manze’s recording (of which I have heard only excerpts) also seems an outstanding choice, peaceful and introspective. And on the wilder side, Riccardo Minasi’s version with Bizarrie Armoniche is also worth a listen; it is certainly never boring!

All those

recordings share a quality which this one lacks: a sense of awe and the

sacred. This Rosary set is competently played but lacks a deep spiritual

core. Where Biber floats up to heaven in mystical meditation, Podger remains

earth-bound. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|