Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

Fanfare Magazine: 38:2 (11-12/2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Les abonnés à Fanfare Magazine ont accès aux archives du

magazine sur internet.

Subscribers to Fanfare Magazine have access to the archives of the magazine

on the net.

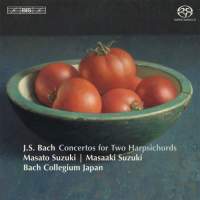

BIS

BISSA2051

Code-barres / Barcode : 7318599920511

(ID450)

Consultez toutes les évaluations recensées pour ce cd

~~~~ Reach all the evaluations located for this CD

After collecting all 55 volumes of Masaaki Suzuki’s Bach sacred cantatas cycle, reviewing two or three of them enthusiastically, and taking personal pleasure in every one of them, this release, featuring Suzuki and his son Masato in Bach’s three concertos for two harpsichords, comes as a big letdown.

I’ll get right to the point. These are wrongheaded one-player-to-a part-performances, a practice which has virtually no currency among serious scholars of Baroque concertante music in general or of Bach’s concertante works in particular. A previous volume of Bach’s violin concertos and concerto for violin and oboe by these same forces was reviewed in Fanfare by Brian Robins in issue 24:2; and in his review, Robins wrote, “In keeping with current thinking, Suzuki has quite reasonably opted for single strings per part, a procedure whose merits are cogently argued by Ryo Terakado in a supplement to the program notes.”

I don’t have that album, so I haven’t read those notes, and I don’t know on what scholarly basis Terakado based his conclusions, but the “current thinking” cited in Robins’s review is now 14 years old; and even if there was a brief fad at the time for one-to-a-part performances, subscribed to by a small number of believers, the practice, even then, was met with significant skepticism from mainstream musicologists and historians, and today brooks little to no support from serious academics.

You can deny history if you wish, but what the historical record tells us over and over again is that when it came to the performance of their orchestral and concertante works Baroque composers tried to scare up as many players as they could find. The period was not one of scaling back forces but of augmenting them. Vivaldi’s all-female band was not a four- or five-girl combo; it was over 60 players strong, and you can be sure that 55 of them weren’t sidelined to polish their toenails while only five of them got to play.

You may say, “Well yes, but this is Bach not Vivaldi.” But keep in mind that one of Bach’s keyboard concertos—the one in A Minor for four harpsichords and strings, BWV 1065, is a transcription of Vivaldi’s Concerto in B Minor for four violins, RV 580 (op. 3/10), from the Italian composer’s L’estro armonico. Does anyone really think that Bach would have performed a concerto for four harpsichords, or even the concertos for two harpsichords on this disc, with a string quintet? The whole balance would be thrown off, and the “concerto’s” principal effect of concertino vs. ripieno would be compromised.

Also, it’s pretty much universally acknowledged that most, if not all, of Bach’s concertos for keyboard and strings are the reworking of concertos for violin or oboe. In some cases, the conjectured originals have been lost, but by no means all of them. You’ll recognize BWV 1062 on this disc, for example, as the popular Concerto for Two Violins in D Minor, BWV 1043. This is not a recent revelation; it’s been known and widely accepted for decades.

Perhaps slightly more recent, however, is the finding that all of Bach’s concertos for keyboard(s) and strings were hastily put together for concerts—some outdoors during the summer months—at Zimmermann’s Coffee House by Telemann’s Collegium Musicum; and in Telemann’s own words—wait for it—“This collegium, despite the fact that it consisted mainly of university students, often reaching a total of 40 musicians, nevertheless could be listened to with great appreciation and pleasure.”

That’s 40 musicians, eight times the number Suzuki uses in these performances. The notion that an orchestra made up of a first and second violin, one viola, one cello, and a violone, the ensemble assembled for this recording, would have accompanied these concertos is absurd. It can’t even be called an “orchestra.” You don’t need to be a music scholar to recognize that; it defies common sense.

These performances sound exactly the way you would expect them to: scrawny strings and a couple of Willem Kroesbergen harpsichords—one after a two-manual J. Couchet, the other, after a two-manual Ruckers—that sound tinny and twang-y. The addition of Masaaki Suzuki’s own transcription for two solo harpsichords of Bach’s Overture (Suite) in C Major, BWV 1066, is an interesting, if ultimately unrewarding, exercise in making a keyboard reduction from an orchestral work, something many composers have done, but usually for pianists to play at home, or in the case of opera and ballet scores, for répétiteurs to use in rehearsals.

As I said at the beginning, this came as a major disappointment after Suzuki’s enlightened and enlivening Bach cantatas cycle. If it’s these concertos played on harpsichord that you’re after, I’d look no further than Trevor Pinnock and Kenneth Gilbert with the English Concert on a five-disc Arkiv Produktion set which gives you all of Bach’s keyboard concertos, plus the violin and violin and oboe concertos, played by an all-star cast of Baroque specialists .... .

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews